Update: Find out more about the 50 Years of Text Games book and the revised final version of this article!

Monster Island

by Jack B. Everitt (Adventures By Mail)

Launched: December 1989

Original Price: $4/turn

Language: Microsoft QuickBasic 4.1

Platform: Pen and paper (mail)

The mailbox squeaks open, and the teenager’s eyes light up: amid the junk mail for parents is a bulky envelope from a company called Adventures By Mail. The teenager has waited all week for it to get here.

Inside is a trifold newsletter and a long stiff postcard, a New York return address on one side and a blank grid of rows with esoteric abbreviations on the other. But the bulk of the content is a stack of stapled laser-printed pages. While everyone getting letters from Adventures By Mail this week got the same card and newsletter, these pages are special. They were printed for one person alone, and describe the fate of the character whose adventures the teenager has dictated for the past few months: a monster named Doggar, who is not a villain in this story but the hero.

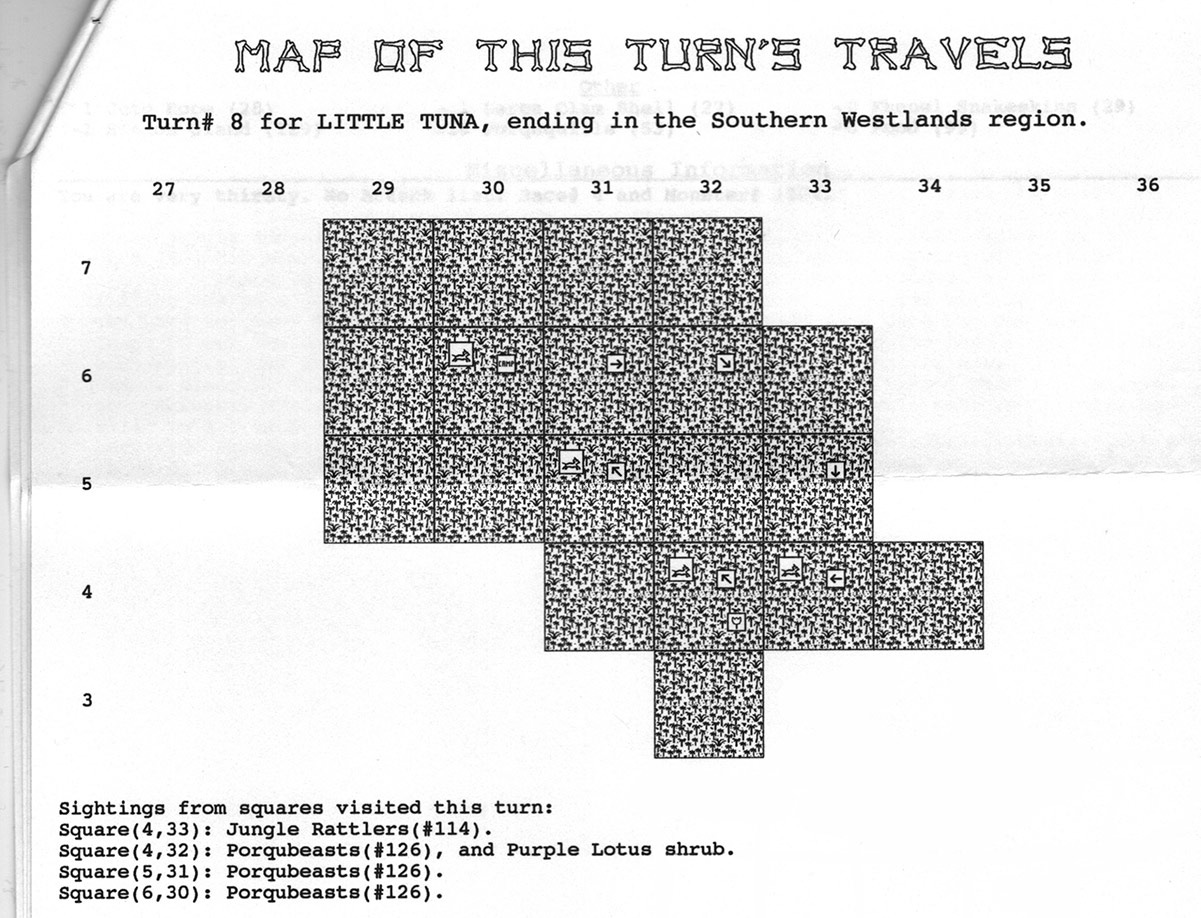

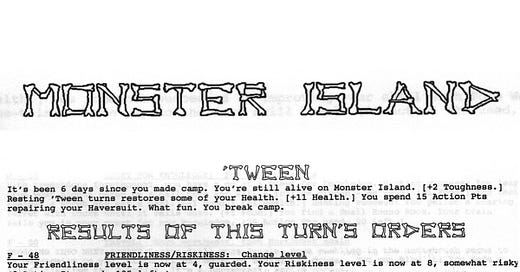

MONSTER# 8489 DAY CYCLE# 8 ACCT# 12067 CREDITS = 6 TURN# 8 WEEK# 11 This turn was processed on MAY 19 at 9:52 AM Your WEEK# 12 will be from MAY 29 to JUNE 9 Your next turn may be run IMMEDIATELY (a make-up turn is due) DOGGAR'S RESULTS 'TWEEN It's been 6 days since you made camp. You're still alive on Monster Island. [+2 Toughness.] Resting 'Tween turns restores some of your Health. [+11 Health.] You spend 15 Action Pts repairing your Haversuit. What fun. You break camp. RESULTS OF THIS TURN'S ORDERS F - 48 FRIENDLINESS/RISKINESS: Change level Your Friendliness level is now at 4, guarded. Your Riskiness level is now at 8, somewhat risky. (0 Action Pts used, 135 left.) T - 33 TRAVEL: Move East, then East again CROSSING INTO NEXT SQUARE(6,31): Still more Jungle. CROSSING INTO NEXT SQUARE(6,32): Still more Jungle. You chow down. (-1 Food.) (20 Action Pts used, 115 left.) J - 15 JAZZERCIZE AEROBICS: For 15 Action Pts You do stretching exercises until you can't stand it anymore. The exercising pays off. [+11 Health, +1 Muscle.] (15 Action Pts used, 100 left.) T - 45 TRAVEL: Move Southeast, then South CROSSING INTO NEXT SQUARE(5,33): The terrain continues to be Jungle. You take a break and chew down a tasty meal. (-1 Food.) CROSSING INTO NEXT SQUARE(4,33): The terrain continues to be Jungle. Uh, oh! A strange smell alerts you to the presence of a Creature nearby. Silently, you squat until all is quiet again. Unfortunately, the Creature keeps coming toward you. It's a Jungle Rattler. (See blurb.) Battle ensues... ** BATTLE: Doggar vs. a Jungle Rattler ** With sweaty palms, you fire one rock toward the Jungle Rattler and connect with it in its upper section. [1 Hit reduces its Health by 4.] Taking a deep breath, you become one with your weapon...

The teen skips ahead to read the new blurb at the back of the stack of pages describing the Jungle Rattler, a creature never previously encountered; then flips back to see the outcome of the battle (Doggar wins) and remaining actions. These include two more fights, a bout of weapons practice, an unsuccessful Quest for Knowledge, and more travel. As the action points run out, results of the final orders from the previous turn are shown:

Y - 23 YELL: Yell# 23 You stick your index fingers in your ears, open your big mouth, and yell at the top of your lungs: "I'm waiting here!" (0 Action Pts used, 0 left.) MAKE CAMP You select a campsite and check out the surrounding area. You hunt for a bit. No luck hunting. The rigors of this week's travels have been of benefit to you. [+1 Toughness.] It's been too long since you last had some water. This lack of water is making you weaker. [-2 Health.] You're no longer able to keep your eyes open. You fall asleep. From the square you washed ashore, you've travelled 34 squares East and 2 squares North.

The next pages shows a map of Doggar’s journey this turn, a grid ten squares wide filled with a black-and-white pattern that might almost represent a jungle if you squint, and overlaid with clip-art symbols for creatures found and objects discovered. Pages of statistics follow, tracking (among many other things) that Doggar has found 40 Knowledge Blurbs, has a 71 Toughness and 42 Muscle, is carrying 3 Small Round Rocks and 1 Large Clam Shell, is very thirsty, and has 152 Action Points available for Turn #9.

It will be a few days before the teenager’s next move. Some thinking is needed to plan next steps before penciling in a new set of orders on the included card. This week’s blurbs must be cross-referenced with others received and carefully cataloged in a basement filing cabinet. There is more to do, too: writing a letter at the kitchen table to a would-be group leader, explaining that Doggar is now waiting in the square they agreed on and hoping the leader can get there in time to perform the promised initiation ceremony; responding to a letter from a Monster met on a previous turn who’d written a polite cursive note asking for any information on Maladors or Ghoul Buzzards. Eventually the small stack of correspondence is stamped and returned to the curbside mailbox. It will be at least a week until the next turn results come back.

Believe it or not, the teenager is playing a computer game.

The genre of play by mail (PBM) games originated with postal chess, where opponents would mail moves back and forth over months of play. By the 1960s a tradition of PBM wargames had started, spurred largely by the release in 1959 of the board game Diplomacy. Requiring exactly seven dedicated players, and released at a time when board games were still frowned upon as a hobby for adults, the game was a natural fit for the asynchronous, private, and distributed mode of play offered by PBM, where players could think about each turn for as long as they liked and weren’t limited to their local area when searching for opponents. In a growing network of fanzines, Diplomacy fans in the 1960s listed their addresses and advertised upcoming games they wanted to run, or announced their availability for games run by others.

Diplomacy is also a game with a focus on negotiation and social strategy, and here too the slower pace of play-by-mail could be an advantage. Some postal games spaced their turns out between months of real-world time to let players mail a flurry of diplomatic missives, threats, promises, and negotiations back and forth before any actual moves needed to be decided on. But stripped of social interaction, Diplomacy is mechanically fairly simple: so some PBM fans began to invent their own original games. (Two of these fans, incidentally, were Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson, whose custom PBM wargames would evolve into Dungeons & Dragons and the dawn of both tabletop and digital roleplaying—but that’s another story.)

In 1970, a young wargamer named Rick Loomis was serving out his Vietnam draft at a fort in Hawaii, and had moved beyond playing PBM games to making his own:

I had invented a multi-player game called Nuclear Destruction which was a little different from Diplomacy in that it had hidden movement. Thus, the moderator had to send different information to each player... All this gaming kept my mailbox full of letters, which was the primary purpose back then. But soon I had over 200 players in my game, and it was becoming difficult to keep up. So I asked my friend Steve MacGregor to write a computer program for me which would run the Nuclear Destruction game. We rented time on a Control Data computer which was near the Fort.

Loomis’s computer-assisted play-by-mail game became wildly popular. The computer allowed the level of detail, complexity, size, and scope of a PBM game to grow far beyond what a human moderator could keep up with. When he got out of the Army, Loomis started the first commercial PBM company, Flying Buffalo, and paid $14,000 for a Raytheon 704 paper-tape computer to process its turns. Years later he’d joke that he might have been the first person in the world to buy a computer specifically to play games with. Outside of specialized applications like military wargame simulations, he may well have been.

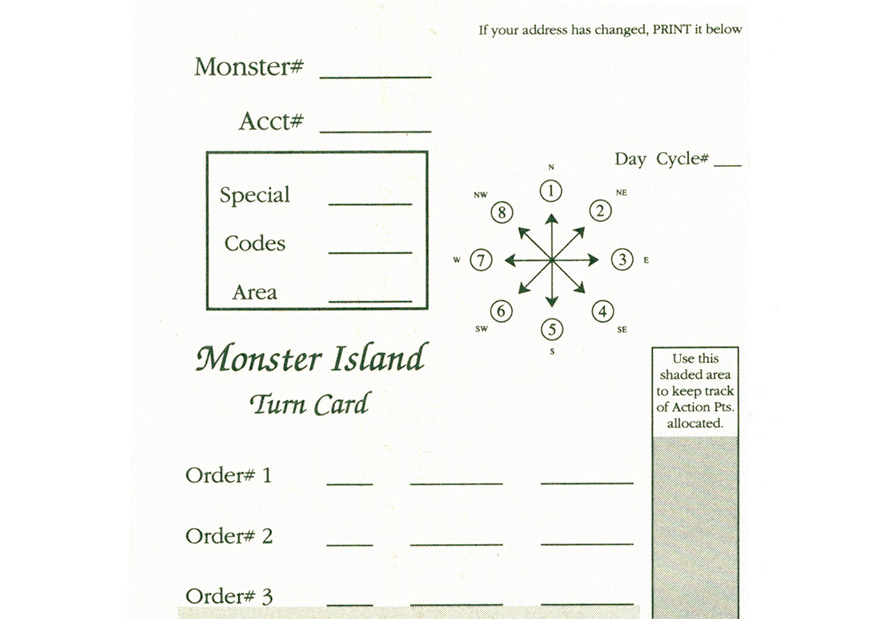

Throughout the 1970s, dozens of other commercial PBM companies sprung up, charging players a fee of anywhere from two to twelve dollars to process a turn in their increasingly elaborate games. While some remained human-moderated, the most elaborate required a computer to keep up with states that might involve thousands of units, each of which might respond to hundreds of possible orders. Some game manuals became inches thick. Each turn, players would submit an order card laying out everything they wanted their units to do, generally with alphanumeric codes that could easily be input into the computer: 47-M-33, for instance, might mean to (M)ove unit 47 east (3) and then east again. OCR technology was still emerging, so an employee would generally type in the orders on each player’s card by hand, a tedious job repeated with each new day’s stack of mail. In some games order results might run to dozens of pages, containing the outcome of multiple actions as well as statistics, information learned, and communications received or intercepted.

PBM games of the late ’70s and early ’80s were far more sophisticated than anything available on personal computers at the time, even for the few players who owned one. One fan would later reminisce about the unique experience of playing: “Board games can’t quite match it, because they’re over in one night and you don’t really have a chance to connive with fellow gamers much. Computer games can’t come close unless they are multi-player, but ultimately fall short for the same reason—they are completed quickly and the pace allows for nothing other than action and grind.” PBM games, by contrast, could last hundreds of turns spread out over years of real-world time, and allow for strategies so complex it could take days to plot them out and set them up.

By the end of the 1980s hundreds of unique play-by-mail games had come and gone, and a new generation of designers had grown up on them. PBM fans Jack B. Everitt, Bob Cook, and Mike Popolizio had founded Adventures By Mail in 1981, hoping to distinguish themselves from a crowded marketplace by focusing on reliability and quality. They had found a hit in their mid-80s title It’s a Crime, where each player controlled a competing gang fighting for turf in a fictional city. The game was cleverly designed to start off simple, with only twelve possible orders, but open up in complexity as a player rose to higher ranks of power, learning new orders to direct minions, create contracts, join or fight the mafia, and mastermind various business ventures. Advertising in roleplaying magazines like TSR’s Dragon as well as publications aimed at sci-fi and miniatures fans, Adventures by Mail hoped to expand the core audience of PBM beyond hardcore wargamers.

Everitt, though, had even more ambitious dreams. While still in the midst of launching It’s a Crime, he had already started planning a “monster of a game—with a whole continent to explore and lots of things to find and make and do. It would have adventure and mystery, and it would never end.” A competitor had recently touted the fact that their system could support a game with 500 players at once. Everitt wanted to make a game that could handle 15,000. Most PBM turn reports were printed on smudgy dot matrix printers, making them all identical walls of text; but laser printers were becoming increasingly affordable, and Everitt had visions of sending players clean reports with crisp text, multiple fonts, and graphical maps. He began coding even though he knew his company could not yet afford the hardware and storage to handle his dream game, trusting the tech he needed would keep dropping in price.

It did. After four years of intermittent work the new game was ready to launch, running on a then-expensive 386 computer and hooked up to a 150MB “Bernoulli box” storage system. The game needed this space: its terrain contained over a quarter of a million locations, each with up to 120 associated variables; there were a whopping 2100 variables allocated for each player character. In December 1989, the first turns for Monster Island were processed, and after a six-month beta with a few hundred players, Adventures By Mail added more laser printers and began to promote the game in earnest.

In the game you control not an army or a fleet of battleships, but a single survivor washed up on the shore of a strange land. You are a Monster, a strong and sturdy (yet ugly and unrefined) explorer of a massive unpeopled island—really more of a continent, described in the manual as “three times the size of Australia.” Rather than issuing single-turn orders to large groups of units, in Monster Island you’d write a sequential task list for a single character, your own Monster. While combat was still present, it was largely outside the player’s control, resolved via randomness and statistics; a relatively minor part of each turn. The game’s focus instead was discovery: through pushing forward into uncharted squares, Monsters could find ruins with buried treasure, learn to craft useful items, trade stories and goods at outposts, build forts, and slowly increase their knowledge about the huge land in which they wandered. And unlike most PBM games that featured a set number of players in a simulation that reset at the end of each run (like a board game), Monster Island was a single persistent world, with each new player washing up somewhere on its western shore, with tougher challenges and bigger treasures to be found the farther east they wandered.

Like It’s a Crime, Everitt’s new game made the clever decision to initially hide most of its complexity. Rather than an enormous rulebook, new players were shipped only a slim pamphlet, laying out in less than 20 half-size pages the game’s premise, instructions, and a starting set of 19 orders. In fact, there were more than 70 possible orders in the game, most of which had to be discovered through play. Reach a trading outpost and you’d learn orders for buying and selling goods; stumble across another player and you’d learn orders for how to be friendly or hostile toward others. You might even unlock the ability to request and send in entirely different kinds of order cards.

One such custom order card was for group management. It’s a Crime had benefited from extensive cross-communication between players, who planned elaborate alliances and betrayals through letters and phone calls: in Monster Island, players could opt-in to having their contact info shared with other Monsters they stumbled across in their adventures. The starter manual explained that a group of eight Monsters could meet in a grid square and perform a ritual that would link them as a Group. Players starting the game at the same time were often placed in clusters near each other: Everitt had added the Group mechanic to the early game to encourage player collaboration from the beginning.

This deliberate design of limited communication and hidden mechanics led to play focused on collaboration, as players needed to correspond and share info to figure out how the game they were playing even worked: its boundaries of geography and possibility, and the capabilities of its complex, hidden engine. At first in the official newsletter, then a smattering of fanzines, players asked each other for help and began to share hard-won info:

Has anyone resurrected (or have information) a ghost?

A monster has heard of demi-gods of Vampires (from ancient silver spike blurb), Gargoyles (from iron spike blurb) and Spiders (from ???). Are there any others? Has anyone found a way to worship or follow one of these gods???

So far I have only noted the following benefits from having a mount. First they will steer you around quicksand. Second a Demon Condor tried to carry me away but my legs had a firm hold on my plodder (mount) and the Demon Condor failed.

Supposedly a Purpumpkin and four Stemtoad glands will allow you to make a lantern. This one definitely belongs in the unconfirmed rumor section.

In a time before personal websites and long before wikis, there was no central storehouse of information about the game or easy way to create one. Adventures By Mail officially frowned on fanzines revealing secrets directly, or reprinting the “blurbs” found in order results, detailing new commands or hard-won knowledge. But within a year of the game’s release, players had begun to self-organize in fanzines like Blood Moon Tribune to create peer-to-peer information sharing networks, and in-game groups whose primary purpose was to learn and explore:

David Gloss would like to create an “information clearing house” for Monster Island. If you’re feeling frustrated, and don’t want to wait to learn something during the normal course of the game, send your questions and an S.A.S.E. to [address omitted]. Also send him any interesting information you have, so he can pass it on to other players.

Jae Kim is undertaking an ambitious task—mapping the entire Island! Send your map data to him at the address below. You can also send Jae an SASE, requesting information on your area; if he can figure out where you are, he’ll send you back whatever information he has, in as much or as little detail as you want.

But the game’s ambitions were perhaps too vast: players had trouble finding each other in all the island’s immense spaces and coordinating across turns that weren’t synced between players (instead advancing whenever each player submitted their next order card, at a maximum rate of once per week). Many fanzine personals show signs of frustration:

PRAALUU: What is your new address? Contact your group leader.

THE BLACK DEATH! Where are you guys? I joined your group and I haven’t met any members in the last 25 turns. Please contact: Bambi the Viper.

It has become sickening that every monster that we have tried to write to neglects to write back after sending very few letters. It distresses us that we take the time to form communications between monsters only to not get a response. If you dumb, stupid, idiotic monsters think that you can get away with this, you have another thing coming. Bounties on the following monsters are set at 50 oculars...

SLIPPERY JEEM - Where are you? I looked and looked and looked and couldn’t find you! Please Yell or make some inscriptions or carve a tree or something! - NAKEMIN T’HED

Years after launch, players had still not uncovered major portions of the game. In late 1992, official organ The Monster Island Journal revealed that only “50 Monsters have successfully performed the Disciple Rite and can now cast spells. They have access to over 40 different spells, although no Monster has learned more than 15 spells.” In 1996, nearly seven years after the game’s debut, an online post announced that a Monster named Skizlum Skallaglamm had become “the first American monster to cross the Crystal Hills barrier,” a range of seemingly-impassable mountains hundreds of squares east of the game’s starting zone, but by no means marking its furthest boundaries.

As fandoms began to move online, Monster Island players gathered on CompuServe’s PBMGAMES forum, GEnie, America Online, and Usenet: the rec.games.pbm newsgroup appeared in 1991. New online communities brought a surge in player communication and information sharing, but perversely were also sounding the death knell for PBM games. Why would anyone pay money to play games via paper mail when email was free? But that doom was still a few years off: the short-term problem was that while players were increasingly online, they were still spread across a myriad of services and standalone communities rather than a unified web, and years away from the collaborative editing technologies that would simplify information-collating for later complex games like Dwarf Fortress or Minecraft.

Monster Island survived nevertheless, and for a surprisingly long time. The reference to American monsters in the earlier quote was due to the game’s popularity in Europe, where UK-based KJC Games had been managing an iteration that had surpassed the US game in popularity, using the same software and terrain but a different database of players. A German version run by a company called Daydream Productions had also launched in 1993. While Monster Island never became the breakaway hit Everitt had hoped for, the US game had over 1600 active players by October 1992, making it financially sustainable in a field littered with the corpses of games that had never made it past their first handful of turns. “It sounds so easy,” wrote Flying Buffalo’s Loomis back in 1983:

get a personal computer, write a program to run your game, put an ad in a few magazines, then sit back and let your computer do all the work while you bank a few extra bucks each week. Unfortunately there are so many problems that are not initially apparent: program bugs, equipment breakdowns, answering rules questions, answering complaints, opening letters, entering moves into the computer, correcting mistakes, moves that arrive late, moves that have unreadable game numbers or return addresses, keeping track of how much money everyone owes, deciding what to do about someone who hasn’t paid the money he owes but is still sending in game turns, handling bounced checks, and on and on. It is easy for a newcomer to get swamped.

Adventures By Mail had overcome these hurdles and survived for over a decade in a brutal industry with minuscule profit margins and customers who were hard to attract and retain. But there were signs by 1993 that Everitt’s interest in Monster Island and PBM more generally had begun to wane. While the fanzines kept coming, no more official newsletters were published after 1992, and a promised Fourth Edition of the slim rulebook never materialized. Improvements to the game continued, but at a slower pace, as Everitt realized the cutting-edge framework he’d started development on in the late 1980s had now locked him into its legacy limitations: “I’m pretty much out of free variables for Monster stats,” he lamented in August 1993. The thought of porting five years of QuickBasic code to a new framework no doubt seemed immensely unattractive.

But the real turning point came that summer at GenCon, the tabletop gaming convention which Everitt religiously attended each year to do outreach and promotion. 1993 was the GenCon of Magic: The Gathering, which hit the industry like a tidal wave: released on August 5th, the collectible card game was all anyone was talking about when the con opened two weeks later. Upstart company Wizards of the Coast sold all the Magic cards they’d brought to the convention within two days, and by October had sold out their entire first printing of ten million cards. Magic became a cultural phenomenon in a way PBM and even roleplaying games writ large never had; Wizards grew so quickly they acquired TSR, the publisher of Dungeons & Dragons, less than four years later.

Everitt, bitten by either the promise of profitability or the intriguing new style of gameplay, started a new venture upon his return from GenCon called Adventures Distributing to sell Magic cards by mail. As he poached Adventures By Mail staff to support it, Monster Island fans began to complain of slow turn processing and slipping customer support. By 1994, Adventures By Mail had turned over management of the game’s codebase to KJC in the UK. By 1998 all the original founders had left, Everitt to expand his mail-order business and start a chain of gaming stores in upstate New York. (He would go on to contribute to both the Dragon Ball Z and Pokémon collectible card games.) PBM was on its way out, anyway, as internet multiplayer gaming swallowed more and more of its player base. Adventures By Mail shut down for good in 2004, having lost most of its players to newer, shinier games.

But Monster Island, like its preternaturally tough residents, refused to die. The game’s European version had amassed a large enough following to form strong ties among player groups, some of which had survived for a decade or longer, still invested in the exploits of their Monsters. By 1999, KJC had “processed in excess of a million game turns with tens of thousands [of] active and satisfied customers.” Introducing the ability for players to submit turns via email, and later receive results that way too, lowered operational costs and provided an easier entry point for new players discovering the game through the internet. In the US, a fan-run upstart operation called Adventurer Guild purchased the servers and rights to run Monster Island in 2005, and kept the US version running for three more years, processing over five thousand turns for a trickle of dedicated players. In the UK, KJC kept the game alive until at least 2017, a run of nearly thirty years for a game its creator had hoped would last for three.

PBM survives today, though mostly in the form of PBEM (play by email). The name of a modern fanzine, Suspense & Decision, neatly sums up the genre’s appeal, captured also by a retrospective on the blog Greyhawk Grognard:

What these sorts of games bring that few others do is time. Time to savor the situation, drink it in, plot and plan. Time to have multiple conversations with folks before you need to get your orders in, and then of course the delicious wait while you scowl at the mailbox wondering why that damned game master hasn’t sent your turn back. You could get that with a PBEM game, but there is also something very viceral [sic] about getting that envelope in your hands and pouring over the results in hard-copy. It’s a very different experience than the instant gratification in modern computer games. It’s also different than a face-to-face game, as the negotiations can get really, really involved and of course the number of potential players is vastly greater.

Though gaming culture has mostly forgotten it, PBM represents one of the oldest threads of digital games. The very first textual computer games were economic or military simulations designed to run on mainframes without interactive terminals. With no keyboards or monitors, input to such programs would take the form of stacks of punch cards, queued to be processed in batch jobs that might not start for days and might take hours to compute. Early games like THEATERSPIEL or The Management Game had core loops much like the PBM games that survive today, with centralized servers processing bulk orders on daily or weekly rhythms: a legacy of digital gaming that stretches back two-thirds of a century. Those mainframe games are impossible to play today, just as most of their PBM descendants have also been lost. While few lived in the right time and place to play them in their prime, the legacy of play-by-mail gaming would be monstrous to forget.

Next week: MUDs get serious, and residents build homes far beyond the looking-glass.

Copious thanks once again to the Internet Archive for preserving many long-vanished PBM sites from the early web. Shoutouts to Monster Island Archive for a comprehensive collection of fanzines, and Jon Peterson’s wonderful book Playing at the World for details on wargaming history. Info on contemporary PB(E)M games can be found at pbm.com and the Suspense & Decision Games Index. Jack Everitt’s most recent venture is Mercator Games; he’s @kreylix on Twitter.

P.S. Flying Buffalo still runs Starweb and Heroic Fantasy games by PBEM, but they have an option for paper turns!

Thank you for covering this topic. Play-by-mail remains a hobby, albeit much smaller than the 1980s and 1990s. You can find out more about the hobby, including an index of 70 available games at Suspense & Decision: http://suspense-and-decision.com