Update: Find out more about the 50 Years of Text Games book and the revised final version of this article!

King of Dragon Pass

by A Sharp

Released: October 29, 1999

Language: C++, OSL (Opal Scripting Language), mTropolis (UI)

Platform: Windows 98, Mac OS 7 (CD-ROM)Opening Text:

There once was a time when gods and people walked the earth together.

It’s “the best game you’ve never played.” It’s “one of the best video games ever made... I’ve never played a video game with a deeper and more engaging world and story.” It’s “timeless... There is nothing like it in the world: a game with a smoothly telescopic scale that alternates seamlessly between fantasy empire-builder and character-driven RPG.” It’s “a tough game to describe... part text adventure, part civilization game, and part choose your own adventure book... it feels like a book come to life.” It’s “an original game design, something all too rare in this world of big-budget clones.” It has “a more convincing illusion of conflict and consequence than anything I’ve played.” It’s “just so different than any other game... it flows like a novel, but one you have a hand in writing... you can play over and over again.” It’s “amazing,” it’s “basically peerless,” it’s “outstanding,” it’s “exceptional.” It is, one reviewer declared, “the game you’ve been waiting for.”

And when it was first released to retail, it bombed.

“Call me shallow,” wrote Computer Gaming World upon the game’s publication in 1999, “but I want gameplay and graphics. And I’ll bet you do, too.” Damningly, the reviewer wrote, King of Dragon Pass “is just a few icons and pretty, hand-drawn screens away from being a text-based game.” At the end of the 1990s, when sales of graphics cards were surging and polygon counts were king, this was a terminal insult: text-based. Asking gamers to pay for words was inconceivable.

David Dunham and his wife Elise Bowditch had not expected such a hard sell. Their game did have graphics, after all: hundreds of screens of hand-drawn art, evocative even if it wasn’t 3D or animated. It had deep strategic gameplay, evolved over three years of development into something compelling, unique, and eminently replayable. And it was set in the world of Glorantha, a fantasy setting popularized by the tabletop roleplaying game RuneQuest with a rich, deep lore and hundreds of thousands of fans. Yet it would be over a decade before the game found its audience and claimed its place as a classic. The story of what went so wrong with the game’s release—and so right with its design and long-term legacy—is a fascinating time capsule of a strange era for video games, poised between the dominance of big publishers and retail stores in the twentieth century and the rise of indies and online distribution in the twenty-first.

Dunham had begun Dragon Pass in 1996, after a nexus of inspirations came together. He’d started programming in the seventh grade (his first game was “a football simulator that ran on an Olivetti 101 programmable calculator”) and as an adult became an Apple developer, working on software for the company’s ill-fated proto-tablet, the Newton. A lifelong board game fan, he was intrigued by strategy video games like Sid Meier’s Civilization which gave players complex simulations and great freedom in how they could interact with them. In particular, a quote from Meier had caught his eye: that “a good game is a series of interesting decisions,” which “must be frequent and meaningful.” Dunham had also been a fan of the complex mythology and worldbuilding of the Glorantha setting for many years, particularly stories of the contested region Dragon Pass, filled with strange monsters and struggling clans. He’d been intrigued too by creator Greg Stafford’s tabletop roleplaying game Pendragon, exploring dynasties and generations rather than heroes in their prime, and had run a mash-up campaign for a while called, naturally, PenDragon Pass. Dunham had started a small software company called “A Sharp” with Bowditch—also a programmer, not to mention a poet. With her encouragement, he began sketching out ideas for a computer game set in Dragon Pass that would merge strategic gameplay, deep lore, dynamic storytelling, and long-term, generational play:

I wanted to have characters get born and then grow up and become heroes, maybe, or in some cases you’ll die of old age. And that scale also helped establish that you were going to have long-term consequences, because it had to be something that could matter ten years later. You know, your kid might have to deal with it.

The game he had in mind didn’t quite fit in any existing genre. It would be more narrative than an empire-building strategy game, but more replayable than adventure games which usually told single, pre-scripted stories. He coined the term “storytelling strategy game” to describe what he had in mind. While he had at first conceived it for the Newton, the idea soon grew beyond the scope of what the handheld device was capable of. Developing games for desktop Macs in the ’90s was financially risky due to their tiny market share, but Dunham and Bowditch found a product called mTropolis that promised an easy way to create cross-platform UI and a release for Windows, too. Securing some independent funding that would allow for hiring contractors to do art, writing, and QA, the two began working on the game out of their Seattle home office in January 1997.

Dunham had been in touch with Glorantha creator Greg Stafford, who provided some design ideas and his blessing, but the real creative workhorse on the project would become tabletop roleplaying designer Robin Laws. Already in the process of becoming one of the industry’s most innovative designers, Laws had written for a number of games (including Earthdawn, Feng Shui, and GURPS) and been part of a push for more “narrativist” roleplaying frameworks that prioritized story over systems. Also a huge Glorantha fan, a chance meeting between the two at a convention would bring Laws aboard Dragon Pass as a writer: so many of his ideas worked their way into the final game that he would eventually be credited as a co-designer. Already familiar with the world’s rich lore, Laws began the work of writing narrative vignettes for the evolving “storytelling strategy game”—in the end, over four hundred thousand words of them.

The game that evolved from the collaboration would follow a clan of Orlanthi, one of several human-like races in Glorantha with Bronze Age technology and divinely gifted magic. Newly arrived in Dragon Pass, your clan struggles to establish a foothold while dealing with vengeful undead, awakening dragons, mystical treasures, and dozens of rival clans with their own agendas. Rather than playing as a specific character, you take a god’s-eye perspective on your clan, setting policies and making big decisions as your people’s story unfolds across years and decades. At the core of the game is a robust economic simulation inspired by one of the earliest text games, Hamurabi: fields, grain, and cattle must be carefully managed to keep a growing population fed. But the engine in Dragon Pass is far more complex, encompassing magic, religion, exploration, trade, and relationships with the many other clans. One review’s list of “stuff you do” in the simulation goes some way toward illustrating its depth:

Selecting and managing a balanced pool of leaders to serve as your advisors on the clan ring (of upmost importance)

Clan mood management, both for your farmers and your warriors - taking actions (feasts, etc.) to increase the mood.

Allocation of crop land vs. grazing land vs. hunting grounds.

Recruitment and maintenance of weaponthanes (e.g. warriors)

Building defenses

Conducting full raids, cattle raids, and aggressions on other clans

Sending exploration parties to nearby or distant places to search for treasures or other discoveries

Erecting shrines to the 20 or so different gods, conducting sacrifices to learn new magic (essentially the games technology tree), etc.

Trade system for trading goods/cows/food or establishing on-going trade relationships.

Diplomacy system for creating alliances, tribes, paying tributes, giving gifts, exchanging knowledge/lore, etc.

Preparing leaders and sending them on “Hero Quests” to trigger special events or gain an unique/powerful advantage.

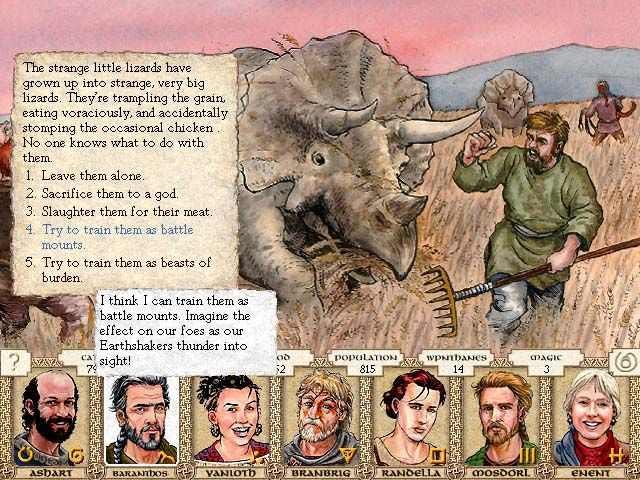

But the simulation is only part of the game. As you take actions, frequent narrative events which the creators called “scenes” interrupt you, seeming on the surface like vignettes from a Choose Your Own Adventure: a paragraph or two of text presenting a conflict or opportunity, followed by a list of choices for how to respond. But what’s happening under the hood is more complex than it seems.

Prominent members of the Bayberry clan come to your clan for help. "This is not a good thing we have to say, but our chieftain, Robasart, has gone mad. He makes foolish decisions, and will not listen to the counsel of the clan ring. We do not want to risk kinstrife, but something must be done. If you agree to raid us, we will make sure that Robasart falls beneath your blades. Then we will owe you a great debt."

1. Demand a specific reward to do as they ask.

2. Do ask they ask.

3. Politely decline.

4. Scold them for betraying Orlanthi values.

5. Send a delegation to warn Robasart of their intentions.

While the text and choices of scenes appear static, they are filled with customization and specifics tied to the state of the simulation. The “Bayberry” clan above, for instance, might have been picked because the player had previously established a friendship with them, and the name shown for their chieftain is correct, one the player might have seen while trading or negotiating. The scene manager has “an awful lot of flexibility in how [scenes] are coded so that they can handle all kinds of situations,” recalls Dunham:

There’s a ton of conditionals, there’s placeholders, there’s a little randomness in them... they won’t be the same any two times, either because text will be randomized, or sometimes responses aren’t available depending on things you’ve done before... In a way you could say, “oh, S-27 is the scene where the visitors from the South show up with their magic instruments,” but that’s not going to be the same any two times because of the other contextual changes.

To help the player make decisions, the game shows advice from your clan’s “ring” of seven leaders, drawn from simulated nobles in the clan—the player can change who sits on the ring at any time, and is encouraged to recruit a ring with a range of backgrounds and perspectives. Each ring member has their own perspectives—they might worship different gods, or have different skills and interests—and each gives advice accordingly.

Renatha: If we succeed in killing their chief, relations with them will improve. If we try and fail, they will get much worse.

Heortarl: They labor under some kind of curse. This could happen again.

Orlgard: If you decide to warn old Mad-Blood, send at least five warriors along with our delegate.

Enderos: Better a specific reward than a vague promise. Maybe they will offer us as many as twenty-five cows!

Offir: Orlanthi are expected to obey chosen leaders. But since Robasart has gone mad, it could be argued that he is no longer the leader they chose.

Harsaltar: Normally I find politics dull, but this is exciting!

After weighing advice from the ring, the player must pick one of the available responses—and each one will change the simulation in some meaningful way. Some might invoke other systems in the game: picking to attack the mad chieftain jumps to the game’s clan warfare screen. Some responses might lead to follow-up questions, bartering over the specifics of a trade or a punishment. Choices might succeed or fail based on hidden tests of skills: a respected leader is more likely to convince her people to take a dangerous action, for instance, and a deception might pit your chieftain’s cunning against your opponent’s. As the results of the scene are shown, leaders might gain or lose prestige; alliances might strengthen or weaken; goods might change hands and seasons will advance. And the new simulation state impacts the pool of what future scenes are now available. If the plan to overthrow the mad chieftain is botched, relations with that clan might plummet, unlocking another scene about a clan seeking vengeance; choosing to do nothing, however, could weaken your chieftain’s prestige and enable a scene where a more forceful leader among your people jockeys for power. Actions have consequences and the player’s choices compound into long-term effects. “By the late game,” one reviewer noted, “every decision you’re making is a result of choices made hours ago, the culmination of events that seem inevitable with hindsight.” One move at a time, each player builds their own unique story of how their clan survived in Dragon Pass—or didn’t.

Surviving isn’t easy. Play reminded one reviewer of “a fairly realistic flight simulator in that you can realize your plane is going down, and you know you need to pull up, but there’s also all these other buttons and switches that need to be hit at the right time and in the right order to make what seems like a simple maneuver actually transpire properly.”

You could have a random occurrence that suddenly leads to a disease outbreak amongst your farmers. The more time your farmers spend in bed sick, the less time they spend producing food for your clan. “Heal the farmers” seems like the obvious answer, just like pulling up in a flight simulator, but it’s not that simple. To heal via magical means, you’ll need to sacrifice to gods. If you’re already low on resources, sacrificing even more can make the situation much worse. Alternatively, you could send out warriors to raid a nearby tribe to steal supplies from them, but the raid could fail, or worse yet, you could over-extend yourself and be defenseless if you get raided while your warriors are out on their raid. You could attempt to go out trading for food, but your caravan could be ambushed or not result in enough food anyway.

The flexibility of the scenes and their tight coupling to the underlying simulation was enabled by a custom scripting language called OSL (Opal Scripting Language: “Opal” was the game’s original codename). Dunham’s goal was to enable “a relatively non-technical author” like Laws to “create files that were almost valid code.” The notion of the scenarios being almost valid was key: the system was so complex that Dunham expected he’d need to fine tune each scene to get it to compile and run correctly. But a clean syntax meant that a non-technical writer could get a scene 90% of the way to compiling, and that target was far easier to design for than a tool 100% accessible to a writer. Speaking to the complexity of the simulation, most scenes were more logic than text. Special functions let each scene easily pick plausible participants for each of its roles:

scene: scene_52politicaltrouble

music: "ItIsBad"

otherclan = BestRelations(KnownClans)

anotherClan = WorstRelations(KnownClans)

c = .chief

y = politician

x = y.leadership

complainer = MaleNameFunctions to cast clans or characters could even be nested. The following line would set c to a friendly neighboring clan with a strong military:

c = StrongestMilitary(ClansWithPositiveAttitude(NeighboringClans))Variables could easily be referenced in the midst of text shown to the player. The extract below follows after forming an initial phrase like “A number of the clan’s leading men” (depending on the gender of the hidden “politician” hoping to cast doubt on the current leader):

text: approach the ring. Their leader, <complainer>, has a litany of complaints. "Ever since <c> became chief," <complainer> says,

text: "<d3:things have gone from bad to worse/this clan has headed downhill/our reputation has suffered>.

text: Our friends the <otherclan.plural> <d4:ridicule our ancestors/tell jokes about us as part of their holy day ceremonies/compare us unfavorably with their livestock/mock us at every chance they get>.Many possible complaints might be situationally assembled, based on the current simulation state and the particulars of your clan’s current leader:

[AntiAldryamiCharacter = c] text: <he/she> sends our weaponthanes into the woods on pointless hunts for the plant-folk.

[ProDragonewtCharacter = c AND (dragonAttitude= 'hostile OR dragonAttitude = 'negative)]

text: <he/she> gives away clan wealth to those fiendish talking lizards.

[ProverbialCharacter = c] text: Half the time when <he/she> says something, nobody can figure out what <he/she> really means.

[WeLostOurLastRaid] text: <c> is unlucky in battle.

z = d3 # Some randomization to the complaints

[z = 1] text: <he/she> sings off-key.Each possible choice can then define the hidden test that controls whether it will succeed, and the consequences. In one option for this scene—disputing the allegations—the chief’s Leadership score is tested against the “Savvy” of the hidden politician behind the complaints:

{

test Leadership(c) vs Savvy x

win: {

text: <c> patiently addressed each of their complaints. <He/She> exposed each one as an exaggeration or misunderstanding, until even <complainer> reaffirmed allegiance to <c> as the clan's chosen leader.

.mood += 20

}

lose: {

text: <c> started explaining <his/her> decisions, but after <he/she> was drowned out by laughter, and then shouted down, <he/she> fell silent.

.mood -= 5

c.leadership -= 0.1

r = true

i = true

goto restart

}

}Each scene also provides many possible bits of advice, distributed to current ring members based on their skills and other aspects of the state. The numbers at the end of each line indicate which of the possible courses of action is recommended:

[Animals >= 3 AND ManyCows] No matter what <complainer> may say, our herds are strong, and that's what's really important. [1]

[Animals >= 3 AND FewCows] I hate to say it, but <complainer> has some good points. [45]

[Leadership >= 3] Somehow, I don't think <complainer> is behind this. [16]

[Leadership >= 4 AND NOT s] <complainer> is acting on behalf of someone. [6]

[Leadership >= 5 AND s] Unfortunately, <politician> does have more of a knack for leadership than does <c>, and will be able to maintain a strong anti-<c> faction if we don't ask <c> to resign. [35]Each scene was a complex miniature program, designed to tightly interface with another complex program—the world simulation—running underneath. Eventually Laws would write over five hundred of them (with other team members, including Dunham and Bowditch, also pitching in). A Sharp established a steady pipeline for thoroughly testing story content. At its peak, twelve people were working on Dragon Pass, including artists who created hundreds of hand-drawn illustrations for scenes. It took far longer than originally anticipated, but after three years the game was complete: total development costs—mostly in up-front salaries, rather than royalties or other deferred payments—came to $500,000. But everyone involved was incredibly excited about what they had produced. Here at last was a truly interactive story, responsive to the player’s decisions, drawing from an enormous pool of content, and steeped in a rich and complex lore. It seemed like a game that might forever advance the state of the art.

The small company’s plan had always been to partner with a big-name publisher for release. As the game neared completion, Dunham hit the trade show circuit, scheduling meeting after meeting with distributors. But the uniqueness of his game proved a curse, not a blessing. Publishers at the time were selling games to retail stores conscious of the shelf space allocated to each company and genre. Retail buyers “were kind of looking for, ‘we need a roleplaying game for this month, and a strategy game for this month, and a sports game for this month, which one do you have for me?’ And this wasn’t any one of those, really.” Publishers thought Dragon Pass was too niche: they literally couldn’t place it on a store shelf. And so, with half a million dollars already invested, A Sharp realized they’d have to publish the game themselves.

At the end of the 1990s, this was nowhere near an easy proposition. While independent gamemakers had been releasing “shareware” for years via BBS, FTP, and the world wide web, or selling direct out of magazine ads and catalogues, few had successfully marketed a big game with a six-figure budget that way. Worse, the rise of the CD-ROM meant the size of a competitive game had ballooned far beyond the bandwidth available to most home computer users who might otherwise have bought one online. Broadband was not yet ubiquitous, with many gamers still connected to the web via dial-up modem. And there were no established digital storefronts yet for videogame downloads, no trusted entities like Itch or Steam to handle credit card payments and protected libraries. Putting a game in a box and getting it into a physical store was still crucial to reaching customers. Yet most retail stores were only willing to sell shelf space to the big publishers with proven track records. Dunham tried to partner with other small Mac developers in a group called Bunch Media in the hopes that collectively they could negotiate for retail placement, but the measure was largely unsuccessful. Retail stores didn’t know who they were, and they didn’t have the cash or clout to force their way in.

So A Sharp got creative. Unable to afford the massive fees to advertise in big-name gaming publications, they took out ads in sci-fi and fantasy fiction mags: one ad in Asimov’s was headlined “Played Any Good Stories Lately?” They made a Dragon Pass demo and got it included on the bonus CDs that came with popular computing magazines. They partnered with local hobby stores to get the game on shelves next to Glorantha roleplaying books. They did direct sales on their website—though then, as now, driving traffic there was a perpetual chore. But having to take all these steps without financial support was a massive challenge: “we didn’t have much cash left for marketing,” Dunham recalls, and he had to take out a loan to fund mass replication of game CDs and boxes.

In October 1999, the game was finally released to mixed results. The very concept of an “indie” game—the term had not yet been popularized—was foreign to many review outlets used to the massive hype campaigns drummed up by mainstream publishers. One reviewer noted the novelty of “a totally unknown game—a definite surprise in today’s world.” The game’s originality, as well as its complexity—it came with a large and necessary manual, in a time when they were rapidly falling out of fashion—also turned off reviewers: one described feeling “overwhelmed” by the amount of freedom the game provided. Worse, it was a game that didn’t show off your fancy new graphics card, a deadly sin in the eyes of many reviewers. Some seemed unable to reconcile their instincts to recommend it with their impression that it was commercially unviable:

It is a fabulous and rewarding experience. Please note however, that artfully presented as King of Dragon Pass may be, there are zero polygons in the entire game and no moving pictures of even the most rudimentary, flipping the top corners of a comic digest form. The game is completely narrative...

King of Dragon Pass is a number of years too late to be a mainstream title. There isn’t even the feedback of moving units on a map a la Civilization. All is static, staid, dull. Still, it has a market. I hope. ...I surprise myself at the length of apologetics that I am willing to stoop for this obscure little game... I’m trying hard to come up with a potential market, but the low system requirements and artful presentation make it a perfect game for many traditional non gamers. It is a game that can appeal to folklorists, historians, old style pen and paper role players, and other people who probably aren’t playing much Quake 3. Who’s going to tell them about it though?

As it turned out, almost no one would. Many major gaming outlets didn’t cover the game at all. Some that did gave it mixed or negative reviews. While some of those folks not playing Quake did find Dragon Pass and many fell in love with it, the game would languish in obscurity for more than a decade.

But the story has a happy ending. Over time, the game’s reputation grew through the slow chatter of word of mouth. It proved fascinating for designers intrigued by the challenge of marrying strong narratives to compelling gameplay, and inspired a small but growing number of further experiments. Among other titles, the popular browser game Fallen London, debuting ten years after Dragon Pass, was heavily inspired by its core mechanics as well as its success in marrying strategic decisions with personal stories:

The temptation in strategy games is to treat everything as a resource. Effective strategic play means taking a dispassionate, high-level view of events. But King of Dragon Pass’ parade of feuds, venality, romance and nobility keep your feet firmly planted in the soil. ...[It] names everyone and everything: ‘Thanes and priests from the Tree Brother clan come to accuse one of your young carls, Yanioth, of secret murder. “We found our revered god-talker Brenna dead in the temple, a dagger in her back.”’ The game never misses an opportunity to remind you that a clan is composed of people, not statistics.

In the 2010s, the rise of digital gaming storefronts and mobile app stores gave indies an increasing number of routes to finding an audience. Even a niche game now had a way to reach would-be fans. Dunham started wondering whether his game, which began as an idea for the Apple Newton, might be reborn on the Apple iPhone. Buoyed by a resurgence of interest, A Sharp released a mobile version of Dragon Pass in 2011 and a tablet version the following year, with the revamped UI and engine making their way back to PC and Mac in 2015. This time, the game would sell, eventually moving nearly a hundred times as many copies as it had in its initial retail run. Twenty years after being derided as embarrassingly behind the times, it now seems incredibly modern: a recent move towards narrative games driven by “storylets” or “quality-based narrative” directly descends from the core Dragon Pass concept of templated scenes both gated by and altering an underlying simulation. In 2018, A Sharp released Six Ages: Ride Like the Wind, the first of a series of planned sequels. The original Dragon Pass now sometimes appears on all-time “best of” lists for both the RPG and strategy genres: having failed to fit into either at first, it now has conquered both.

“It sometimes takes many in-game years to become obvious,” one modern review wrote of playing Dragon Pass, “but this is a world that never forgets.” He meant to invoke the way decisions in the game can come back years later with surprising consequences, but the statement might apply just as well to the real-life story of how A Sharp’s game became a classic. Sometimes it takes some waiting for the right scene to come around before seeds planted ages ago can grow.

Next week: a game on a pedestal, unveiled in a most unusual art show.

You can buy King of Dragon Pass for PC on GOG, which also includes the original 1999 release; it’s also available for various other platforms from the official A Sharp site. Thanks to the Internet Archive for hosting the many ‘90s gaming magazines from which review excerpts were taken, and to David Dunham for extensively blogging his game’s history and development process.

Way back in the day (and I mean *way* back in the day) I was fortunate enough to be a player in one of David's Runequest campaigns. His worldview was rich, detailed, innovative, and *consistent*, and he incorporated all of that (and more) into his design for KoDP. The game was so deserving of praise and attention, but the timing as pointed out in this fine overview just wasn't right. I'm glad that all the hard work by David, Elise, Robin Laws, and all the other talented people involved has finally gotten some of the recognition it so warmly deserves - and thank you for spreading the word.

I played that in 2000--by that time I had gone Linux only at home, so I bought another HD and installed Windows in a dual boot, solely for that game.

Besides a good story and good gameplay, the thing I really liked about Dragon Pass was the characters and world didn't seem like modern world citizens with modern individualistic values simply transplanted into a primitive fantasy world. It felt like a genuinely foreign world in a different time. The thanes had different motivations and agenda from the farmers or carls. Another game I ended up playing while I was still running windows was Black & White, the god game, which really suffered in comparison to Dragon Pass--I was hoping for the same thing, but it was nothing but a videogame with generic videogame characters (god or human).

I bought the sequel recently on Steam, but didn't check the reqs--no Linux version. Someday I'll install a Windows VM and get around to trying it.