This article on a fascinating 1980s text adventure adaptation was originally commissioned by David M. Rheingold, and appears in a modified and expanded form in Further Explorations, the companion book to 50 Years of Text Games. Here’s the original version: enjoy!

When computer games were young, no one was sure what they might grow into. Were they the first step to immersive interactive movies? Digital version of tabletop roleplaying or board games? Were they better at game or story, more highbrow or lowbrow, genuinely new or just electronic recycling of traditional media? As various branches of the entertainment industry began to notice computer games as a medium, each tried to shape the conversation about them to its own benefit. When the publishing industry began to investigate the world of digital games in the early 1980s—quite logically, since many were still mostly text—they naturally tried to turn them into interactive books.

In 1984, in certain more progressive bookstores, you might have found digital text games for sale promising interactive versions of analog bestsellers in the same store. Often featuring a famous author's name prominently on the cover (like Isaac Asimov, Ray Bradbury, or Anne McCaffrey) these “bookware” titles—text adventure adaptations of famous novels—tried to thread a tricky needle. They had to appeal to both computer game novices and existing adventure gamers, capture the spirit of a famous story, and do it with only a fraction of the word count (and rarely any input from the original author). They had to take stories never designed for interactivity and find a way to shoehorn it in, hopefully without twisting the source material into unrecognizable shapes.

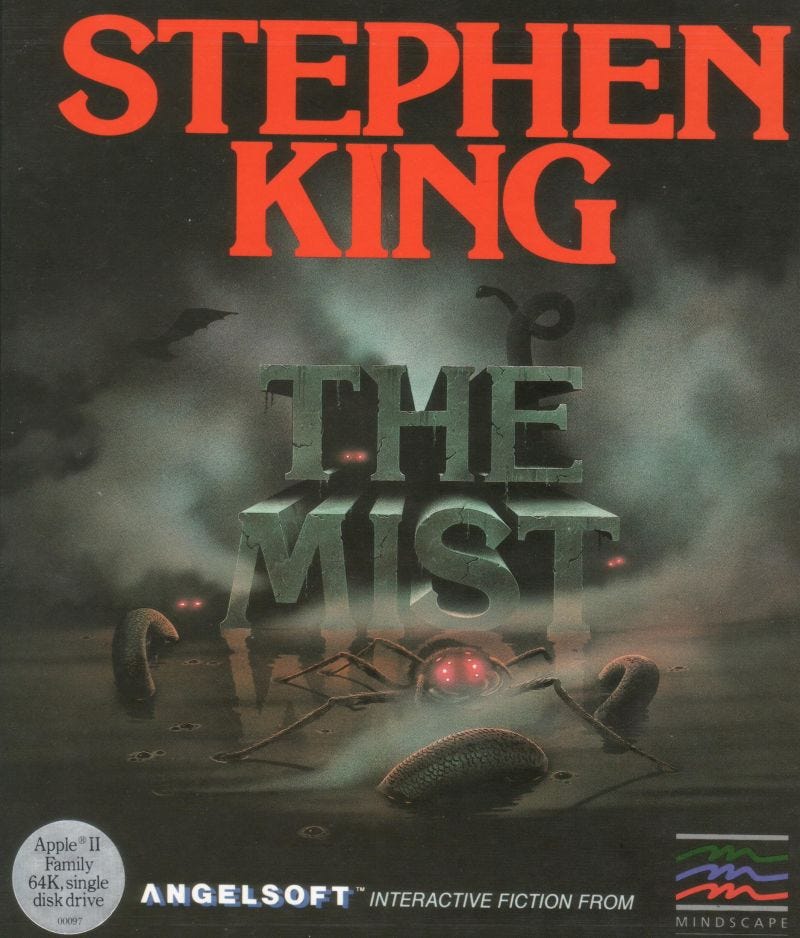

It was not an easy task. Many bookware titles proved frustrating to design and unsatisfying to play. One representative example might be Stephen King's The Mist, developed by a small company called Angelsoft and published by Mindscape in 1985. Like many bookware games, it faced significant challenges in turning a compelling work of fiction into a story the reader is expected to play.

Angelsoft was founded at the peak of the short-lived bookware boom, destined to be on its way out by the time of The Mist's release. A venture of children’s author Mercer Mayer and business partner John Sansevere, the company hoped to reach an audience beyond computer gamers by licensing adaptation rights to well-known books. Their first big deal landed somewhere between serendipity and the luck of the draw: Mayer had an existing connection with Stephen King, but the horror author’s career was so red-hot that the only story he could offer not already licensed elsewhere was a somewhat obscure novella, which had never been published as a standalone title. But King’s name alone was enough to turn heads, so the story was duly licensed—a move which helped Angelsoft gain credibility to make further deals (such as one to write official James Bond adventure games).

Writer Raymond Benson was brought on board to tackle the design and writing for both the King and Bond adaptations: as with most other bookware, King wasn't involved other than via an introductory phone call with Benson. Benson had experience adapting stories to the stage as a writer and theater director, and had done some scenario design for tabletop roleplaying games; Angelsoft probably hired him more because of his existing work on the Bond franchise than for any connection to King. A fan of board games, roleplaying games, and text adventures, Benson was excited to tackle the challenge of a digital adaptation, even given a tight three-month development cycle—The Mist was announced at the summer 1985 Consumer Electronics Show, and expected to be on sale that holiday season.

The original story, first appearing in 1980 in the anthology Dark Forces, was not as well-known as King's novel-length hits like Carrie, The Shining, or Pet Sematary. But The Mist was well-regarded by those who’d read it, nominated for both World Fantasy and Locus awards in the wake of its release. Like many of King’s early hits, it uses a simple, primal fear—something in the mist—as an engine to drive a tense and well-told story pitting everyday people against terrifying supernatural forces. The plot centers around a group of small-town residents trapped in a grocery store when a dense white mist rolls in. It soon becomes clear the mist hides hideous and hungry creatures; though its nature is never explained in the story, there are hints the mist connects to a secret government program in the nearby woods called the Arrowhead Project. Much of the story hinges on how friends and neighbors trapped in the store react to this apocalyptic scenario: are they driven by fear to barbaric behavior, or can they hold onto their humanity enough to band together and survive? The central character, a father fighting to keep his young son safe from terrors both outside and in, makes it through a series of deadly encounters that pick off the supporting cast one by one. In the end, driving off into a mist that may or may not ever end, he gives up a chance to rescue his wife in the hopes of keeping his son safe instead.

The text adventure adaptation distills the story down to its core plot beats, and can be divided into two main parts. Skipping the original’s lengthy prelude about an unseasonably powerful storm, the game begins in the grocery store just as the mist has appeared and claimed its first victims. You play the father from the story, but in this version your son is absent and your goal is to reach and rescue him—presumably a decision made to avoid the difficulties of coding a realistic companion NPC. In the game’s first part, you explore the store and surrounding buildings to scavenge everyday items (a box of salt, a can of insect repellant) that can be used to defeat four wandering monsters in the misty rooms outside (the salt dissolves a creature with a “horrible slug-like body”). Several characters from the story wander through the grocery store rooms, and you can interact with them in a limited way. Most notably, the story’s Mrs. Carmody, a religious fanatic who slowly convinces more and more survivors that the mist requires a human sacrifice, here represents a ticking clock that gives you only a limited number of moves in the store before your character is selected for “expiation.”

The game’s second half bows more to typical adventure game conventions, diverging from King’s story as a consequence. After clearing out the wandering monsters, you’ll infiltrate the secret government base, which here is more definitively identified as the source of the mist (and given the more ominous name “Project Plague”). Inside its halls and on your way to rescuing your son, you face a few tougher versions of creatures you’ve already defeated, which you must destroy by upgrading your weapons (giving up a can of bug repellent for a sprayer filled with military-grade insecticide, for instance). Once the final terror is dispatched with, you rescue your son and drive off into the endless mist. It’s a more heroic final act than in King's original, but as a game design it nicely introduces a core mechanic (finding the weakness of each monster) and uses it consistently across the game.

In theory, at least. In practice, The Mist is rather frustrating to play. This was true upon the game's original release—MacUser’s review noted “This game is hard”—but due to changing conventions and some quirks of emulation, the game has become even more of a challenge to play today. Much of the difficulty can be laid at the feet of its untested parser, newly created by Angelsoft at the time, and the understandable desire to make it seem as competent (or more so) as competitors’ engines which had already had years to mature. Behind several of the game's rough patches can be sensed design decisions that doubtless seemed like clever ideas at the time but serve mostly to frustrate the player. A misunderstand command, for instance, often produces an atmospheric rejection instead of an error message, which at first might seem good for immersion:

-> start truck

Take a deep breath and try again.

-> search truck

Who knows what could have happened to Billy by now...

The game’s manual bills this as a feature: “No matter what you enter, you always receive a response.” But in practice, it just makes it harder for the player to learn which commands are valid (compare to a more traditional message like “I don't know the word 'search'.”)

This is especially problematic in cases where the expected syntax or commands don't conform to conventions that text adventure players were then (or are now) familiar with. The game's instructions were split between two printed reference cards included in the original package—a generic one for all Angelsoft text games, and a Mist-specific addendum—and these are rarely included with digital versions of the game available for download today as abandonware or through online emulation, even though both contain vital information for playing.For instance, you'd need Angelsoft's “Introduction to Interactive Fiction” booklet to know that you can only successfully interrogate an NPC by ending your command with a question mark, or that you might need to CAREFULLY EXAMINE some objects, not just EXAMINE them (neither feature is common in interactive fiction). But you would need the separate manual specifically for The Mist to know that in this game, you might need to tell some characters to CALM DOWN before they'll answer you. You can’t learn these command formats from within the game itself, so without a copy of both manuals, you’ll miss key objects and find yourself unable to proceed. Combined with a few other oddities—the verb TAKE is recognized, for instance, but not GET—the game is borderline impossible to play today without a walkthrough, even for text adventure veterans. (You can find both manuals here; and for good measure, here’s a walkthrough.)

It gets worse. The Mist’s monsters both move and attack at random, possibly a design decision made to make the game feel more dynamic and replayable. Your own gunshots also succeed or fail randomly, and since monsters kill you with a single attack, just one unlucky moment in any fight means game over: so saving your game before any encounter is vital. But another unfortunate side effect of modern emulation based on a quirk of period hardware makes saving your game nearly impossible while playing today. The problem comes from the fact that The Mist didn’t support dual disk drive setups, where the player would have the main game disk in one drive and a blank floppy for saves in another. This meant players in the 80s would have needed to swap the program disk back and forth with a save disk—but this kind of hot-swapping is not well-supported by emulators today. The need to constantly save was merely frustrating on the game's first release, but now adds another layer of difficulty for modern players. With no ability to save and restore, even following a walkthrough religiously offers only a tiny chance of a successful playthrough.

These issues with emulation and modern play are not The Mist's fault, of course (though it's interesting how they intersect with the game's design decisions). A more fundamental issue with The Mist, both then and now, is that it’s not particularly scary, and this is largely because it fails to manage a key element of successful horror—tension—in either its prose or its code. To start with the prose: while Stephen King had the luxury of a much larger word count (not to mention years of experience writing horror fiction specifically), Benson had the thankless job of hacking that carefully sculpted prose down to a size that would fit on a floppy disk along with a game engine. The need to constantly stop the action to ask for the player's input also made it harder to slowly build up a sense of creeping dread, something the original story did quite effectively. The result is that while many core incidents of King's story appear in the game, they’re stripped of much of their effectiveness. Compare a moment from the original where the grocery shoppers first begin to realize something has gone wrong:

Things began to happen at an accelerating, confusing pace then. A man staggered into the market, shoving the IN door open. His nose was bleeding. “Something in the fog!” he screamed, and Billy shrank against me—whether because of the man’s bloody nose or what he was saying, I don’t know. “Something in the fog! Something in the fog took John Lee! Something—” He staggered back against a display of lawn food stacked by the window and sat down there. “Something in the fog took John Lee and I heard him screaming!”

The situation changed. Made nervous by the storm, by the police siren and the fire whistle, by the subtle dislocation any power outage causes in the American psyche, and by the steadily mounting atmosphere of unease as things somehow... somehow changed (I don’t know how to put it any better than that), people began to move in a body.

They didn’t bolt. If I told you that, I would be giving you entirely the wrong impression. It wasn’t exactly a panic. They didn’t run—or at least, most of them didn’t. But they went.

An equivalent sequence from the game's opening text:

As you glance up once more, a teenager, his tattered clothes flapping wildly, bursts into the store screaming:

The fog! It got Mark! Oh my God, it...

Before anyone can ask him what he means, he wheels around and runs back out. [...]To the east, several people are grabbing all the baked goods, and in the beverage section to the south someone just knocked a soda bottle out of Mrs. Reppler's hands.

In another example, the amorphous monsters that come out of the mist are hybrid creatures that seem to combine familiar and alien elements. From King:

It was a flying thing. Beyond that I could not have said for sure. The fog appeared to darken in exactly the way Ollie had described, only the dark smutch didn’t fade away; it solidified into something with flapping, leathery wings, an albino white body, and reddish eyes.

The game, by contrast and the necessity of its engine, must reduce each creature to a noun the player can type in to refer to it, leading to a series of monsters introduced with evocative prose but thereafter referred to with somewhat reductive and deflating labels: the Bug, the Spider, the Bird.

But it’s not just the compressed text that strips the digital Mist of tension; it's the game’s very structure. Other than Mrs. Carmody’s countdown in the grocery store, there are few mechanisms within the game for creating a sense of rising tension. Instead, most threats are introduced and resolved immediately, either in cutscene blocks of text that begin and end before the player can react, or in instant deaths as a result of a bad random check:

The Bug is here.

-> west

The Bug jumps onto you and attaches its sucker pad to your body. Its bile begins to dissolve your flesh, and with a wet, slurping swallow, the creature disembowels you.

The nightmare is over, for now...

Would you like to play again?

Compare these sudden deaths to the 1981 game 3D Monster Maze. What could have been an uninspired maze escape game, navigated in blocky black-and-white from a first-person perspective, is enlivened considerably by an opening message providing a disturbing context: you're trapped in the maze along with a hungry Tyrannosaur that's hunting you. “THE MANAGEMENT ADVISE THAT THIS IS NOT A GAME FOR THOSE OF A NERVOUS DISPOSITION,” the intro text warns. “IF YOU ARE IN ANY DOUBT, THEN PRESS STOP.” As you explore the maze, a series of single-line messages appear at the bottom of the screen, your sole indicator of how close the monster is to you at any given time.

REX LIES IN WAIT

HE IS HUNTING FOR YOU

FOOTSTEPS APPROACHING

/RUN/ HE IS BESIDE YOU

And finally…

Though the language is as minimalist as possible, here your grisly death is foreshadowed, teased, anticipated, and savored: upon your demise you are “SENTENCED TO ROAM THE MAZE FOREVER.” While The Mist does include ambient messages about strange sounds and half-glimpsed tentacles, these are not sequenced in any particular order, nor are they connected to anything happening in the game’s simulation. As a result, you soon learn to ignore them, since they never impact your actual play.

Horror in games was still a developing concept: only a handful of earlier titles had tried to seriously explore it at a level beyond surface theming. Later games with sound and graphics had other ways to elevate the audience's heart rate, while later text games could incorporate both far more prose and far better designs, as early technical limitations dropped away and craft wisdom accumulated. Michael Gentry's Anchorhead, released thirteen years later, would become a well-regarded classic as an example of what a scary interactive fiction game could aspire to. Though less well-regarded, The Mist was a noble and pioneering effort. It’s been cited as an early example of the survival horror genre due to its use of item-based puzzles and limited ammunition. King's original story, which Angelsoft’s game helped keep in the public consciousness, would later inspire more successful games: the creators of both the Half-Life and Resident Evil franchises called the story a key inspiration.

Raymond Benson would continue writing for games for a time—his best-remembered work is probably as lead writer on Ultima VII, regarded by many fans as undisputably the entry with the best story—before continuing on to a successful career as a novelist. He was a founding member of the International Association of Media Tie-In Writers, and has authored dozens of books (including twelve official James Bond novels). In the early 2000s, he wrote a handful of books set in the Splinter Cell and Metal Gear Solid universes, making him the rare author who has both adapted a book into a game and a game into a book. On adaptations, he’s said that “It’s not really a consideration to make it ‘my own.’ These things are always work-for-hire jobs and the job is to adapt it the best way we can and keep it faithful to the original. Maybe we put in something that is a little bit of ourselves.”

But “more often than not,” he concluded, “it’s unintentional.”

If you enjoyed this article, you can find it in an expanded form as a chapter in Further Explorations covering the challenge of adapting books to interactive fiction (and discussing playable versions of everything from the Monty Python cheese shop sketch to Shakespeare’s The Tempest). The rest of Further Explorations includes coverage of visual novels, one-room games, hacking sims, and wordplay games. And the main 50 Years of Text Games: From Oregon Trail to AI Dungeon book is still available: a deep dive through the first half-century of interactive fiction, covering everything from MUDs to hypertexts to VR poetry.

I'm looking forward to reading this!

(It's not in my paper copy of the kickstarted Further Explorations, but maybe it was added to digital versions later?)

Good write up, Aaron! Much appreciated. (Also, glad it's in the expanded Further Explorations, but happy to get to it here.)