Update: Find out more about the 50 Years of Text Games book and the revised final version of this article!

[Content note: mention of implied rape in context of historical fiction. Spoilers for one of four endings, getting onto the deck of the pirate ship, and signaling the Helena Louise.]

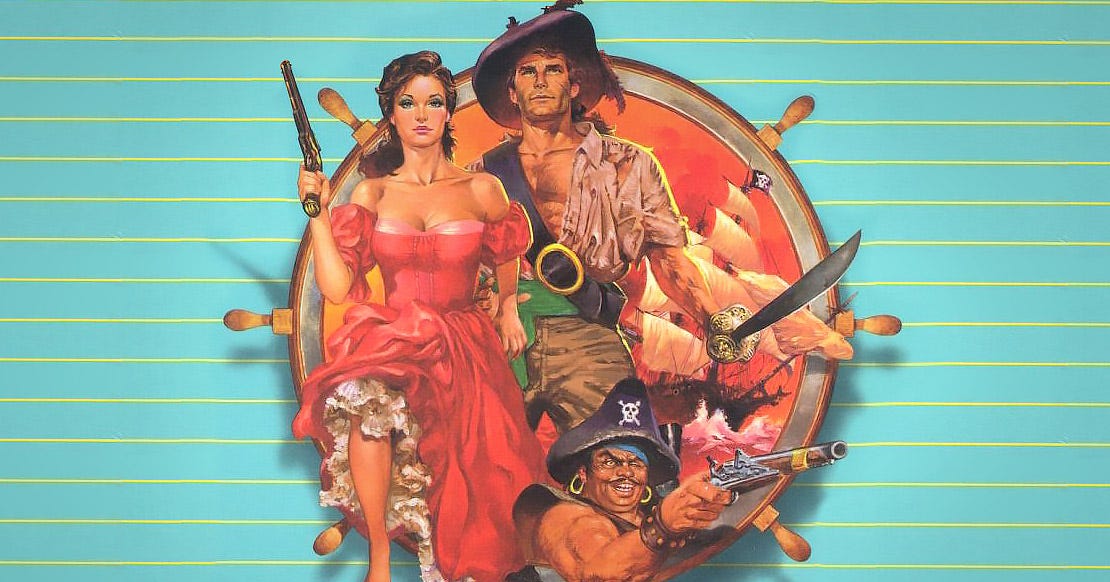

Plundered Hearts

by Amy Briggs

Released: September 1987 (Infocom)

Language: ZIL

Platform: Z-machine v3Opening Text:

>SHOOT THE PIRATE Trembling, you fire the heavy arquebus. You hear its loud report over the roaring wind, yet the dark figure still approaches. The gun falls from your nerveless hands. "You won't kill me," he says, stepping over the weapon. "Not when I am the only protection you have from Jean Lafond." Chestnut hair, tousled by the wind, frames the tanned oval of his face. Lips curving, his eyes rake over your inadequately dressed body, the damp chemise clinging to your legs and heaving bosom, your gleaming hair. You are intensely aware of the strength of his hard seaworn body, of the deep sea blue of his eyes. And then his mouth is on yours, lips parted, demanding, and you arch into his kiss... He presses you against him, head bent. "But who, my dear," he whispers into your hair, "will protect you from me?"

“Yuk!” began the review in Commodore User magazine of Infocom’s latest text game, something new for the company and, perhaps, for the reviewer: a romance. “Probably Infocom’s easiest title,” it concluded dismissively, in a tone matched by many other critics of the day. “There is, of course, a place for easy adventures,” wrote Computer and Video Games magazine: “after all, everyone has got to start somewhere.” Everyone here presumably meant women, the only plausible audience for an easy game with kissing. Many male reviewers assumed the game was a cheap attempt to expand Infocom’s audience to a new, less sophisticated demographic: a “two-fisted attempt to attract more female purchasers,” said an Atari fan mag. Many uneasy jokes were made about whether male readers were really expected to try playing a game that starred a lady. “Can it be enjoyed by someone other than a member of the fairer sex?” asked one. “Certainly—if you don’t feel strange reading about your craving for the arms of another man.” A British computer mag asked “Will the challenge of the game make a man of you? Or... will abandoning the trousers for a cotton frock give you a kick worth nearly £30?”

But Plundered Hearts had not been created via marketing dictate, and Infocom’s audience had never been exclusively male. Amy Briggs, its author, was one of many women fans of the company’s games (even the hard ones). She had first discovered text games via the Adventure International titles before moving on to Infocom’s more sophisticated fare, finding Suspended an especially intriguing challenge. Through an accident of timing, she graduated from fan to employee quite abruptly: just after finishing college she’d moved to Boston to crash with her sister, and on the first day she opened a local paper she saw an ad from her favorite game company looking for testers. Two weeks later, she was working there.

Briggs had grown up in rural Minnesota—one of her first jobs had been as an usher on A Prairie Home Companion—and since high school she’d been a huge fan of romance novels, reading them “in great quantities.” She’d even thought at one point that writing them might make a nice career. In college she’d majored in English with a specialty in British Literature, but also taken computer science classes, so she’d felt both qualified and interested when the Infocom job popped up. But Briggs didn’t want to remain a tester. She started staying late on evenings and coming in on weekends to teach herself Infocom’s in-house programming language ZIL, and at the encouragement of Steve Meretzky, built a sample game—an Alice in Wonderland pastiche about a game tester assigned increasingly surreal tasks—to demonstrate her proficiency. In two years, after a lot of hard work, she’d achieved her dream of becoming one of Infocom’s famed Implementors: the writer/designer/coders who were the creative force behind the company’s interactive fiction. At age 24, she’d gotten a greenlight for her first game.

It was Briggs’ idea to make the game a romance, a mode Meretzky had cautioned her against tackling first (since people were the most difficult part of an interactive story to simulate). It would be Infocom’s first in the genre, as well as its first game written by a woman and its first with a female protagonist. It would, in fact, be one of the first mainstream games of any sort that dealt with love from a feminine point of view, rather than the prurient or infantilizing perspective of most previous games about women, mostly by men. Women designers were still seen as oddities in a domain increasingly coded as masculine: the extent of this can be felt in a 1988 column by a male industry analyst who wrote that Briggs’ game was the first where you played as a female character (it was not) and that Briggs might be “the only woman working in the field” (she wasn’t). But the fact that a mainstream columnist could make these claims speaks to the abysmal lack of visibility for professional women in gaming. Each one had to act like a pioneer. Each one had to accept that their every move would be second-guessed by the men around them, as well as many of the women.

Plundered Hearts leans heavily into the genre conventions of historical romance, the books sometimes called “bodice-rippers” where young women meet dangerous men and, though kept apart by unassailable social conventions, assail them nonetheless. The game’s backstory sets you up as a dutiful young gentlewoman of the 17th century whose father, the aging Lord Dimsford, has been kidnapped by the villainous governor of a Caribbean isle, Jean Lafond of St. Sinistra. As the story begins, you’re rescued from one of Lafond’s lackeys by a dashing pirate captain, an unlikely ally of your father’s:

A tall form blocks the shattered door, one fist still raised from striking your attacker. You catch a glimpse of the hard masculinity of his broad shoulders, the implied power in the scar that etches the stranger's jaw, and feel tremors course through your veins. Then you realize how ragged are his shirt, patched breeches and high boots. Intuitively, you understand -- he is the dreaded Falcon, scourge of the sea! Alas, your fate is sealed. Resigned, you meet his sea-blue eyes. >slap him "Please, I'm not trying to hurt you," the stranger says, casually deflecting the blow. To your surprise, the stranger bows. "Well met, my lady." His accent is cultured, his smile vibrant. "I am Captain Nicholas Jamison, known in these waters as 'The Falcon'."

Jamison plans to help rescue your imprisoned father and settle an old score with Lafond, but traitors among his crew are working against him. In the end, it’s mostly up to you to effect the rescue, in the process working your way through a delightful set of pirate adventure and historical romance tropes: climbing up trellises, discovering secret passages, dancing with the handsome men and drugging the goblets of the lecherous ones, swinging from chandeliers, and narrowly avoiding exploding barrels of gunpowder.

While most previous games had made little of the player’s gender, explicit or otherwise, Lady Dimsford is heavily constrained by the conventions of both her genre and historical period. Early on, for instance, you need to escape a shipboard cabin through a shattered window to climb up to the deck:

The end of a rope ladder blows past the window. >climb onto ledge You climb onto the ledge. The ladder drifts within reach. >grab ladder You put everything in your reticule and reach out for the ladder and over-balance, tumbling from your perch. Your hand closes on a slimy hemp rung as you fly out over the waves, clinging tenuously, feet free, to the ladder. On the Ladder You are clinging to a slimy ladder, tied to a rail of the poop deck above you. Not far from your feet, waves kiss the stern of the ship. >up In these clothes? You jest. All air is driven out of you as the ladder slams into the stern. >examine myself You are wearing a cotton frock, very pretty, if a tad outmoded for today's fashions.

If you climb back inside and remove your frock, revealing “a linen chemise and a few layers of unmentionables,” you can climb the ladder successfully. But arriving on deck so undressed results in “a fate worse than death” when the lecherous pirate crew sees you. To move freely about the ship, you must first find a male disguise—a pair of breeches and a shirt, discarded by a cabin boy.

Puzzles in Plundered Hearts tend more towards the pragmatic than the enigmatic. The game often allows alternate solutions: there are several different ways to break into Lafond’s estate, and several possible uses for a garter belt. In one scene, you need to signal a ship at harbor from the window of Lafond’s manor, and are meant to do this with a chipped piece of mirror found much earlier, using it to reflect the brilliant moonbeam shining in through the window. But if you forget to bring the mirror with you or never discovered it, the same scene involves a butler serving food on a “mirror-bright” silver tray:

>wave tray in moonlight You scrape everything off the silver tray into the bushes below. You roll the silver tray around in the beam of moonlight till it glows silver-white. After a moment, a flash of light responds from the Helena Louise.

The puzzles are also more tightly coupled to plot than in most previous Infocom games, serving more as gates between sequential dramatic scenes than sundry challenges in an open environment. “This is not a romp through a lot of puzzles but a voyage through an interesting story,” Briggs wrote at the time. Games historian Jimmy Maher has noted that the game has “a plot thrust—a narrative urgency—that’s largely missing elsewhere in the Infocom canon.” While the company often described their games as like “waking up inside a story,” Maher says Plundered Hearts approached that ideal more closely than nearly any other of the company’s titles, with “many more of the sorts of things the uninitiated might actually think of when they hear the term ‘interactive fiction.’”

As you play, the plot thickens, events unfold, relationships change, characters develop and deepen, romance blossoms. In short, real, plot-related things actually happen. I don’t mean to say that this is the only way to write a compelling text adventure. Nor do I mean to say that there’s a lot of plot here by the standards of a typical novel... What I am saying is that Amy Briggs took interactive fiction as Infocom preferred to describe it and made her best good-faith effort to live up to that ideal.

Though constrained by space—the game was stuck with Infocom’s old z3 file format, not the expanded z4 afforded Meretzky on A Mind Forever Voyaging)—Briggs stuffed every corner of the disk space allotted to her with color and character. The code often takes situational advantage of the game state to add nice bits of genre-appropriate color, such as when you try to climb a ship’s rigging while carrying a dagger:

>up You bite down on the dagger, freeing your hands to climb. When you stop, you take it back again. The wind, a mere breeze on the deck, blows more fiercely.

This even extends to the game’s disambiguation and system messages:

[Which pirate dost thou mean, Captain Jamison or Crulley?]

>save Aye-aye.

And the game delights in letting you lean into the conventions of the genre: shrieking at timely moments, slapping people who deserve to be slapped, and dressing up in fancy clothes—in a first for Infocom, the game contains a thousand-line source file to simulate the various dresses, breeches, brooches, and hats you might encounter. Briggs even worked in responses to appropriate verbs that might not have been attempted in most previous Infocom games:

>swoon You've never been missish enough to faint on demand.

>sigh You sigh contentedly, smiling.

Plundered Hearts, in short, asks you to embody and perform a role that’s laden in a genre’s gender stereotypes. Few previous games had done this so consciously, and not everyone was willing to play along (as we’ll come to shortly). But it’s worth noting that Briggs certainly did this deliberately, and often pushed back against tropes in both obvious and subtle ways. While the dashing Captain Jamison is ostensibly the hero of the story, he’s actually not very effective at pretty much anything, and to complete the game you’ll need to take matters firmly into your own hands. Jamison, in fact, must be rescued by you, not once but several times. And in the game’s final moments, one of four possible endings is to abandon him on the beach and commandeer his ship:

The tale you tell Jamison's crew, of rapine and blood, of your heroic attempt to save their captain, and of your own escape after his death in your arms, is not so far from the truth that you cannot appear sincere. Cannily, you take advantage of their temporary grief, select a private guard, and teach the rest the discipline of the whip. In 253 turns, you have achieved a score of 25 out of 25 points. Thus you have finished the story of PLUNDERED HEARTS, earning the title, "Pirate Queen."

“I’ve had some people write that the hero is a wimp,” Briggs once noted. “I personally like to think of him as a sensitive wimp.” Some have viewed the game as more tongue-in-cheek critique of romance novel tropes than reinforcement of them. It’s hard to take seriously, for instance, its near-total replacement of the traditionally frequent adventure game deaths with sequences like these:

Dragoons surround you. Something cracks over your head, knocking you unconscious. You awaken, cuddled in a huge purple and gold curtained bed, with a shocking migraine. The man lying next to you pays no heed to your complaints, and commands you in French when you try to defend yourself. He tires of you within a few weeks, but lets you work the streets of Santa Ananas. *** You have suffered a fate worse than death ***

A brig, Portuguese by its sails, rescues you. The sailors are brown skinned and smooth, and the first mate, the ship's and yours, is gentle. They leave you in Rio, alone and forgotten. *** You have suffered a fate worse than death ***

While conscious she was writing in a genre rife with stereotypes about women, Briggs seemed less concerned with deconstructing its tropes than having fun with them, and writing a kind of story she’d always imagined it would be fun to tell:

C. S. Lewis said he had to write the Chronicles of Narnia because they were books he wanted to read, and nobody else had written them yet. Plundered Hearts was a game I wanted to play. ...In general I like stories about strong heroines. I like those stories more when the heroines are not above falling in love. ...One doesn’t have to be Miss Simper to enjoy dancing (or necking in the gazebo) or be Ms. Rambo to defeat the bad guys. Just be yourself, and do both.

But not all women were willing to give the game the benefit of the doubt. “At the time there were some critical reviews that just hated it because of its over-femminess,” Briggs remembered in 2010. “I remember one reviewer just lit into the game because she was trying to karate chop and to do tough guy stuff and the game wouldn’t let her, and so she was criticizing it for not allowing the character to be strong.” The reviewer in question was actually Janet Murray, a professor who would go on to write Hamlet on the Holodeck, one of the most influential academic texts of the 1990s on interactive storytelling theory. Murray wrote of the game:

It’s hip, it’s clever, it’s tongue-in-cheek. But it’s not feminist. ...Romance fiction is focused on the image of the powerful, violent male and the helpless maiden. It’s obsessed with female virginity and male potency. Briggs observes all those conventions.

Other women reviewers, sensitive perhaps that they’d been assigned to cover the game because they were women, also took issue. Well-known columnist Scorpia wrote “Right up front, I’ll tell you that when I heard Infocom was putting out a gak romance adventure, my stomach did flip-flops. This is not to say that romance doesn’t have a place, just that its place is not in adventure games.” (She did admit it was “not so bad as I expected.”) Betty DeMunn, writing for Atari Age, praised Briggs for offering the chance “to shed ‘him’ and become ‘her’” for a change, but ultimately gave the game a negative review, her first ever for an Infocom title:

Plundered Hearts disappointed me. The intent is to be applauded. Women have long been overlooked, both as authors and consumers, but to grab us, you need a stronger hook. Let us be what we are today, or will be in the future—not what we were 300 years ago. ...Being a feisty old feminist, I have to say that Plundered Hearts is one small step for womankind, sideways.

Combined with the tendency of some male reviewers to dismiss or trivialize the game, Plundered Hearts seemed destined to be a commercial failure. Its release came at a troubled time for Infocom: the company was in dire financial straits. Only a few years previous it had been a popular studio on the cusp of widespread cultural relevance: coming off the massive success of Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, profiled in Time and Newsweek, and praised by celebrities like Robin Williams, who supposedly called up co-founder Marc Blank in the middle of the night for hints. But graphics were at last taking over games for good. Infocom’s sales had been plummeting. A long-in-the-works but disastrous attempt to pivot the company to business software proved a failure, in the interim starving the games division of R&D money that might have helped them add meaningful multimedia to their titles. An acquisition by Activision, which had seemed like a good partnership and safety net, turned sour after a new CEO there micromanaged Infocom into the ground: among other questionable decisions, decreeing that the company’s long-successful practice of promoting popular catalog titles should be jettisoned in favor of fresh boxes on store shelves each quarter—which meant accelerating the pace of new releases to an unsustainable pitch. By 1987, the company was down to less than thirty employees from a height of over a hundred. Briggs, in fact, was one of the last to be hired.

The result was enormous pressure on the remaining designers to deliver a success: and not just any success, but a blockbuster huge enough to save the company. Briggs recalled:

There was a panic underlying everything of “where is the next Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy? ...go out and just write us another game that will sell 150,000 copies.” Which none of the other games had done except for Hitchhiker’s... It was this impossible task that was laid on. “We don’t want to burden you with telling you what to do. You just write us a hit.”

Infocom marketing went a little overboard with the game and what Briggs described as the “by a woman, for women” angle: the back of the box gushed that “in the 17th century, the seas are as wild as the untamed heart of a young woman,” and claimed that “In PLUNDERED HEARTS, Infocom brings your wildest fantasies to life.” Yet the company was also desperate to convince manly men that they’d enjoy the game too, and it’s perhaps no surprise that in the end, few customers of any gender were convinced to give it a try. None of Infocom’s games were selling very well any more. The company that had once affixed to its door a plaque reading “Imagination sold and serviced here” was finding fewer and fewer buyers.

“I came in at the end of the good stuff,” Briggs recalled decades later, but considered even the company’s twilight one of the best times of her life. “It was the best job I’ve ever had... it was really not a job, it was an amazing creative experience... something very special and unusual.” In another interview she said “We were all young, creative, humorous, enthusiastic people, we loved what we were doing and we enjoyed our own games more than anything—and that shows in the games themselves, I believe.” At 24, Briggs wasn’t much younger than most of her fellow Implementors, and open office doors meant ideas were often kicked around with colleagues. Design and coding advice were swapped freely, at lunches or on walks taken to workshop awkward puzzles or dig a character out of a story hole. “It was everybody working on their own thing,” Briggs recalls, “but together.”

But declining sales and a continuing lack of corporate support meant the end was coming. In 1989, Activision effectively shuttered Infocom, laying off half its remaining employees and offering the rest the chance to relocate to a West Coast office. Only a handful accepted. Briggs had already left, after a frustrating period of being shuttled from one half-baked project to another: she’d pitched games based on the Anne Rice vampire novels and Dr. Who, but management was floundering. The “good stuff” was over.

While a critical and commercial dud in the 1980s, Briggs’ game has been fondly remembered. Plenty of young women could overlook the flaws in its representation for the sheer novelty of having some, and fewer men today are afraid to admit that “abandoning the trousers for a cotton frock” can be pretty fun. Many reviews even at the time were positive—one called it “a wonderful adventure, bursting at the seams with atmosphere, interesting puzzles and tense situations”—and the game’s focus on story over puzzles proved ahead of its time, forecasting the turn most amateur interactive fiction would take in the decades to come. “Plundered Hearts is one of Infocom’s more underrated games,” a 1990s retrospective noted; 2000s IF writer Emily Short called it “almost pitch-perfect... has a lot more plot than most other Infocom games, and often feels surprisingly modern.” In the 2010s Jimmy Maher, who covered the entire Infocom canon extensively for his blog The Digital Antiquarian, called Plundered Hearts one of his favorites: “in terms of sheer entertainment I don’t think Infocom ever made a better game.” And in 2020 Jon Ingold, of successful story-driven game studio Inkle, called it the best of the Infocom titles. “It’s stunningly good,” he noted:

It’s one of the few that manages to put its fiction above its puzzle-solving at all times, the whole way through. When I think back to that game I don’t remember a single puzzle, I don’t remember a single moment of friction. What I remember is dressing up and dancing at the governor’s ball, and hiding behind a door and whacking someone on the head with a box in order to escape. I remember moments of swashbuckling... When I look back on it I remember having been on an adventure rather than having played a game, and that’s such an achievement.

Briggs never made another game after leaving Infocom, though she’d meant to spend some time writing the proverbial “great American novel.” For her goodbye party, her coworkers made her a t-shirt that read “1989 Winner of the Pulitzer Prize.” “I was asked, ‘why can’t you write the Great American Interactive Novel,’” she recalled, “to which I responded that characters are the stuff of great novels, and that realistic character was a great weakness in interactive fiction.” She didn’t end up writing the book, but went back to school to get a PhD in Experimental and Behavioral Psychology. Her dissertation was about how readers understand character in stories.

As of 2021, her LinkedIn proudly listed her volunteer work at a local library. Some passions, indeed, are hard to quit.

Next week: Across an ocean and a continent, teenagers in a Communist country discover that underground text games are a completely uncensored medium.

You can play Plundered Hearts via the story file and an interpreter program like Lectrote, or in an online DOS emulator. The feelies, manual, and source code are also available. Most major sources are linked inline: unattributed Amy Briggs quotes are from either a New Zork Times interview or her unedited interview for the documentary “Get Lamp”; special thanks to Jason Scott for making that footage available.

Definitely one of my very favorite Infocom games. It's a shame Ms. Briggs never made another game, as she definitely had a feel for how to create true interactive fiction, especially how to handle plot. I wonder if she knows about modern authoring systems like Inform and the like? Maybe she could be convinced to try her hand again...

Being 12 at the time, I didn't want to play a pirate game where I didn't get to play the pirate (and had to play a girl at that). Was very much in Fred Savage "Is there kissing?" mode (appropriate as The Princess Bride came out the same year). That said, a year or so later, I recall playing through Moonmist as both male and female, so apparently like Fred, I grew to not mind it as much.

Honestly, reading the end brings back the bad memories of watching Infocom fall apart in real time. They, Epyx, and Atari - the games companies of my youth - all seemed to blow up right around the time that Commodore ultimately did, and it was sad times.