Update: Find out more about the 50 Years of Text Games book and the revised final version of this article!

Digital: A Love Story

by Christine Love

Released: February 28, 2010

Language: Ren'Py

Platform: Windows/Mac/LinuxOpening Text:

Using Your New Modem Message from: Mr. Wong |Reply| Hey, Lucy, so you have your computer set up. I thought for Mr. Carlson's kid, I'd throw in a little something extra: there's a dialer for your modem attached to this message. If you plug it into the phone line, you can use it to dial BBSes. Just make sure not to run up your dad's phone bill with long distance calls, OK? Here's a local BBS I recommend looking at: 698-5519. Enjoy, George Wong Wong Computers Download attachment: dialer.exe 421 bytes

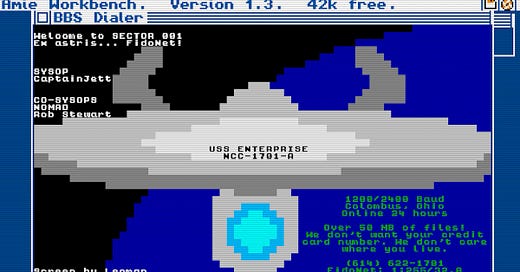

Connecting to a BBS—a bulletin board system, the primary way to find online communities before the mid-1990s—meant punching in a phone number and waiting for your modem to negotiate with a distant computer. The dial tone, the beeping digits, the screech of connecting hardware would give way, after a sustained pause (and if all went well) to the glorious sight of a colorful ANSI welcome screen drawn line-by-line across your monitor. Once granted an account on a new board, you’d gain access to a new pocket dimension of games, downloads, discussions in progress, and—potentially, occasionally—new friends. Finding boards—new virtual islands to explore—was a bit like scavenging for buried treasure: here a new number casually mentioned in a forum post, there a FILE_ID.DIZ with a new board’s digits in its footer; or maybe a private message from a buddy sharing a less advertised system like a whispered invitation to a speakeasy. Some boards weren’t meant for you: you were too young or too clueless or too civilian to be on them. But the adventurous could learn to crack passwords or spoof calling cards, slipping between cracks in the system to venture into illicit cyberspaces. Anything seemed possible in an online world discovered one node at a time. The globe feels larger island-hopping than staring down at a flattened Mercator projection.

It’s an experience very different from browsing the modern web, one which few people too young to have lived it can easily appreciate. Digital: A Love Story recreates it in loving detail, capturing the texture and flavor of BBS life remarkably well. But its author never experienced that life firsthand. In the year the game is set—1988—she hadn’t even been born.

Christine Love grew up in small-town Canada in the 1990s and early 2000s: but she really grew up on the internet, among the first generation for whom the web was a constant and ever-present “third place.” She had learned some programming in school and found making computers do neat stuff was compelling, but loved writing even more, spending more of her time online with fellow writers than coders. As a teenager she’d discovered the digital game genre called visual novels, which married dialogue-driven storytelling with character artwork, sound, and music—especially popular in Japan, and often used to tell stories focusing on love and romance. While some visual novels have branching stories or stats that must be raised to win, many don’t, and Love appreciated that this lack of obstacles reduced the frustration and skill-based gatekeeping in other kinds of digital story. It freed authors and readers to focus on other ways computers might impact the art of traditional fiction writing: simply “having the power to punctuate prose with music and animation,” Love wrote, “is really interesting.”

When Love discovered visual novels in the mid-2000s, the genre was in the midst of an English-language renaissance brought about by a new tool making it far easier to create them. Called Ren’Py, its name was a play on both ren’ai—the first word in the Japanese term for dating simulators—and Python, the maturing programming language it was built around. Created by American Tom Rothamel, Ren’Py was first released in 2004 as a special-purpose tool evolved from the more general Python gamemaking library pygame. One of the chief goals of pygame had been to create a free and cross-platform engine that could abstract all the difficult OS-specific tasks of handling images, sounds, and animation into a simple library that let gamemakers focus on higher-level concerns. Ren’Py built a series of domain-specific languages on top of this framework, making it easy for visual novel authors to write scripts that could easily be compiled, along with all their multimedia assets, into standalone binaries for Windows, Mac, and Linux. Inform had been a similarly democratizing tool for creating text adventures, but since visual novels were structurally simpler, Ren’Py authors could write in a syntax almost as natural as a screenplay—while more experienced coders could tap into the full power of Python if needed.

e = Character('Eileen', color=(200, 255, 200, 255))

label start:

$ renpy.music_start('sun-flower-slow-drag.mid')

scene washington with fade

show eileen vhappy with dissolve

e "Hi, and welcome to the Ren'Py 4 demo program."

show eileen happy

e "My name is Eileen, and while I plan to one day star in a real game, for now I'm here to tell you about Ren'Py."

e "I can tell you about the features of Ren'Py games, or how to write your own game. What do you want to know about?"

label choices:

menu:

"What are some features of Ren'Py games?":

call features from _call_features_1

jump choices

"How do I write my own games with it?":

call writing from _call_writing_1

jump choicesLove first got involved with the Ren’Py community through an annual tradition started in 2005, inspired by NaNoWriMo—National Novel Writing Month, in which aspiring novelists try to write a novel in thirty days. The Ren’Py version was NaNoRenO, and challenged community members to create a complete visual novel during the month of March, releasing it on the 31st. Like the parser community’s annual IF Comp, NaNoRenO became a popular yearly event, inspiring often sixty or seventy new games each year. Love first took part in 2007 at age 17, and released a new game each March through her first years of college, appreciating both the esprit de corps of a community event and the useful pressure of a deadline: “if I don’t set one,” she once wrote, “I tend to work on something for two weeks and forget about it forever.”

The game jam vibe also made it easier to find collaborators, more common for VNs since a wider range of skills was needed to make them (including writing, coding, art, and music). Approaching what would have been her fourth NaNoRenO in March 2010, Love had found an artist collaborator and an idea for a game. But she also had a second idea, one that didn’t need character art and which she thought she could pull off by herself. She decided to write it during February, before NaNo season kicked in, and release just before the jam started as a treat for the community. She thought it would “probably get about as much readership as I normally got, which was about a dozen or so people; less, because it was kind of a crazy idea about an obscure part of computing history.” It would turn out to be the most popular Ren’Py game ever made at that point, and one of the first to crossover into mainstream success.

Love’s “crazy idea” wouldn’t end up looking like a traditional VN at all. Rather than colorful character portraits, the interface would be almost entirely text—specifically, it would mimic the famous blue tones and blocky letters of Workbench, Commodore’s 1985 answer to the original Mac OS, which had launched with their influential Amiga 1000 computer. Love’s aim was to tell a period story about forming strong relationships online in a time when that had still been a rare and special thing: “when everyone’s on the internet,” she noted, “it’s a little less interesting.” While at first she planned gameplay based on mechanics from hacking simulators like the 2001 classic Uplink, as her ideas evolved she found herself streamlining out the systems to focus more on the story and characters. “It’s a cyberpunk story that’s romantic instead of gritty,” she would later say. “Instead of being a hacking game about hacking, it’s a hacking game about talking to people.”

RE: First Poem Message from: *Emilia |Reply| I do suppose you're right. Thanks, I appreciate your directness, I'll have to keep that in mind for my next attempt. To tell you the truth, I'm really glad you replied. Nobody else really had anything worthwhile to say; just some compliments that were obviously false, and asking if I really was a girl. Why would anyone ask a question like that? But you seem nice, Sapphire, and much better than that. Thank you.

The game’s interface mirrors the text-only structure of a BBS, primarily unfolding in public and private messages across a handful of different systems. As you learn to navigate your computer and the boards you can connect to with it, you strike up a friendship with a fellow poster called *Emilia which soon blossoms into something more. The inherent awkwardness of a budding romance mediated by technical limitations is recreated with sometimes painful accuracy, as in a moment where you’re disconnected just as *Emilia confesses her feelings for you.

But the plot thickens when you learn your online crush has a secret. The story soon dives down the rabbit hole of a strange yet familiar alternate history for the early net, a world “five minutes into the future of 1988” filled with unstoppable viruses, secret government projects, and ghosts in the machine.

While many visual novels and interactive fictions give players a choice of what to say during conversations, Digital offers only a binary switch: you can click Reply on any message, or ignore it. The player sees only the response that comes later (if it comes at all) and not their character’s own words, a deliberate design choice of Love’s: “It doesn’t break the immersion as much as if you would see your response and say, ‘wait, I wouldn’t say something like that.’” The reader must fill in their own side of the conversation in their head, and the slow, interrupted cadences of the asynchronous dialogue helps capture the feeling of plausible replies to half-remembered posts.

Tell me Message from: *Emilia |Reply| I've been talking too much, I know, I'm sorry. Make me feel better about being so self-centered by telling me about yourself, okay? How are you doing? [user clicks "Reply" and closes the message window.] Messages Tell me *Emilia |Open| RE: HELP! VRAM overflow Rocky |Open| RE: Nihao, bitches! Rainbreeze |Open| RE: Notepad (Amie) Ward |Open| VRAM overflow Rocky |Open| The Matrix registration System |Open| RE: Lack of downloads Figaro |Open| RE: The Next Generation Tiberius |Open| RE: RE: Cryptic *Emilia |Open| RE: Cryptic *Emilia |Open| RE: Self-Confidence *Emilia |Open| RE: Computer Viruses *Blue Sky |Open| [user reads a few more posts] Alert New private messages downloaded! |OK| [click] RE: Tell me Message from: *Emilia |Reply| No, I didn't know at all. I try not to make assumptions about anyone. It's silly, don't you think? Anyway, I'm sorry to hear it. I'm sure you'll figure out what to do with your life next soon enough. And I know what it's like to be lonely, believe me.

Unlike many visual novels, you’ll need to solve a handful of puzzles to complete Digital: though most are gentle. A dangerous bug in your operating system needs to get patched with help from a friendly techie before it can be turned against you; you’ll exploit a flaw in another system’s password generator to gain access to a forbidden system. Much as with the real early internet, the universe of boards you can connect to expands through trading info with fellow explorers, slowly growing your personal index of phone numbers and scribbled passwords:

RE: Lack of downloads Message from: Figaro |Reply| Well, Lake City Local isn't really about the warez or hacking or any other illegal stuff. You know, the Sysop here doesn't really want to get himself arrested or anything. You could always check out The Matrix at 220-7683. That's where I always go, anyway.

Rather than automating the process of connecting to each board, Digital makes you painstakingly dial each one by typing in a phone number, waiting through the sound of your simulated modem connecting, and entering the right password for that board. As the game progresses and you frequently jump between systems, you’ll do this over and over, often with the added complication of a spoofed long-distance calling card. It takes work to get through the story, even though it has only one path and doesn’t branch: “I’ve just never had an idea for a story that had two satisfying endings,” Love wrote shortly after the game’s release, “but I’ve since realised there’s more to it than that:”

there’s just a whole lot of emotional power in immersing the player in the story by making them interact with it. ... You can just watch someone solve a mystery, but that’s not nearly as fun as feeling like you’re solving it yourself. To read about [the BBS] world is one thing, but to actually be thrown into it... that’s actually evocative. That gets you into it much more than any prose could.

Love had researched BBS life in part through an extensive archive of old posts collected by computer historian Jason Scott at textfiles.com. “I just read a lot of absolute junk posts,” Love recalled, “hours of just reading through archives... trying to nail people’s voices.” Amidst the messages advancing the game’s plot are a host of others:

I'll be here less Message from: Acid Queen |Reply| Hey, guys, I'm afraid to say that I'm going to be posting here a lot less in the upcoming months. A LOT less, actually, probably not at all. I'm sorry, but anyone who was looking forward to more of Neon Empire will have to wait a while. The thing is that little Ichigo's due just about any day now...

RE: He doesn't get it Message from: Hollinger |Reply| You're missing the point entirely. SF isn't supposed to be predictive just for the sake of predicting the future. It's not supposed to be a crystal ball. There's an extrapolative aspect, yes, but even the most extrapolative stories also have strong metaphorical qualities, and Gibson is no exception...stdlib.h error Message from: Figaro |Reply| Every time I try to build something with <stdlib.h>, no matter what I do-- even the simplest program!-- it always throws the error "incompatible types in assignment at line 322"! What the hell is going on here? Does Amie C just plain old ship broken, or what?

One reviewer wrote that the background noise of the game’s setting helps make it, among other things, “a celebration of the Internet,”

and of the communication—and community—it enables. Obviously, the game’s plot and premise would be impossible without the Net—this is a digital love story, after all! But it’s the incidental detail, the stuff that has little or nothing to do with the plot, that makes the tribute clear. It’s the distinct culture of each BBS you visit... you won’t mistake the friendly Lake City Local for some of the places you encounter later in the game. It’s the messages you read, and the characters who post them... It’s the friendships some of these characters have formed—relationships that existed long before the player character showed up, and that will hopefully go on long into the future. It all rings utterly true.

“As an era it fascinates me,” Love recalled. “Everything seemed so much more isolated. ...This is very much a story about an adolescent searching for some sort of connection, and I think putting it in the ’80s, putting it on bulletin board systems, really helps that.”

While the player types in a name for the silent protagonist whose gender is never specified, Love had imagined her as a woman. The Ren’Py community had been a more welcoming space for queer creators than many other indie or professional game scenes—roughly two-thirds of forum posters were women, and many identified as something other than straight—and Love’s earlier NaNoRenO titles had all featured same-sex romances, challenging the assumption that the default love story should always be hetero. “The protagonist’s gender [is] up to the player to decide,” she wrote of Digital and its sequel:

So I guess they could be about a heterosexual player... but that was never my intent; my intent was to make a game for people like me. It’s just that it’s possible to do that without excluding others for no reason.

“And you know what?” she added, in a dig at a game industry still complaining about the challenges of supporting diverse character models and plots: “It really was not that fucking hard for the writing to accommodate that.”

It’s hard to remember now, but as late as 2010 same-sex romance was still almost unheard of in mainstream games. Gay marriage had only recently been legalized in Love’s home country of Canada, and was still six years away from becoming federally recognized in the United States. In 2011 it was newsworthy when BioWare included prominent queer romance options in Dragon Age II (“I am so sick of talking about BioWare right now,” Love would lament). On the forums of Star Wars: The Old Republic the previous year, the words “gay,” “lesbian,” and “homosexual” were blocked, not long after a guild for LGBT players had been banned in World of Warcraft. Gamers and gamemakers in these communities were fighting not only to survive but to even get platforms to admit they existed, and the success of Love’s projects would make her a fiercely outspoken voice for queer content in games.

It would prove to be the beginning of an unexpected career. “Honestly, the idea of being considered an indie game maker never even occurred to me until well after I finished Digital, and others started to throw around the term,” she noted years later. “To me it was just a fun little writing project that couldn’t possibly appeal to many people other than me.” But some combination of nostalgia, representation, unique mechanics, a good mystery and compelling writing turned Digital into a viral internet success. “[It’s] my favorite indie game of the year so far,” one reviewer wrote. “What other game lets you crawl BBSes, uncover conspiracies, commit telephone fraud, and fall in love in just a couple hours?” Love soon found herself writing an ambitious conceptual sequel set thousands of years in the future, exploring the databanks of a generation ship whose once-enlighted culture had descended into brutal misogyny, modeled after the real-life Joseon Dynasty in medieval Korea. Analogue: A Hate Story would become a longer and deeper story than Digital: Love would drop out of college to complete it, founding a company to market her “weird unsellable feminist visual novel,” whose website described it as “a mystery featuring transhumanism, traditional marriage, loneliness, and cosplay.”

It was not the typical formula for a bestselling game. But Analogue would again earn widespread acclaim for its writing, its sophisticated storyline, and a refined UI that still centered text but gave it a sleek, modern interface. It proved successful enough that Love found she could make a living writing her games. Her work, one critic wrote, has often been “the antithesis of the modern power fantasy”:

Instead of growing a spine and taking down a great evil, her games are more about people allowing themselves to become vulnerable and become close to someone else. ...She wants to make games that explore emotions beyond triumph, and she’s been doing just that for years, attracting a growing cult following in the process.

Love’s success selling games that center writing, women, queerness, and “cuteness”—part of her ethos of “coming from a place of sincerity”—has inspired other designers to focus on aspects of the human experience that traditional games neglect. The obsession with graphics and photorealism in the mainstream industry, as one example she’s cited, can be an unfortunate distraction from crafting more meaningful experiences. “Realism is about presenting the world the way you see it,” she says. “But I’m not concerned with what you already see. I’m concerned with what you’re not seeing. ...a lot of stuff I do, I deliberately exaggerate. I find that subtle is sometimes useful, but very rarely, frankly.”

“I always thought I was going to be, like, a novelist,” Love once mused, “and have to support myself doing some shitty programming 9-to-5 job while I worked towards getting published.” For her fans, it’s been a blessing that Christine found games before some big publishing house found her.

Next week: - universe + galactic supercluster + galactic supercluster + galactic supercluster + galactic supercluster…

You can download Digital: A Love Story for various platforms, though Mac users today might have better luck running the Windows version through Wine. Unattributed quotations inline were taken from 2010 interviews with Christine Love for Resolution Magazine and at The Next HOPE. You can find out more about visual novel engine Ren’Py at renpy.org, and find Christine Love online at loveconquersallgam.es or on Twitter @christinelove; her latest game as of this writing is Get In The Car, Loser!

Absolutely fascinating, and I'd never even heard of this story. Thanks so much for writing about it!

I will say, though, that I grew up in the (real) BBS era, and I miss it sorely. Between the door games, downloadable content (esp games you could run on your own computer), and the fumbling friendships with people with odd "handles" (a term, I believe, that came from the early Citizens Band radio craze) was just incredibly cool.

Best of all, due to the expense (in those days) of long-distance calls, most folks on your favorite BBS were usually local to your area, which led to some very awkward but amazing meetups (face to face), sometimes between people of wildly disparate ages. I still remember going to one BBS pizza restaurant meetup, wondering which person was "ArchMage5" and if their looks would match their online personality.

Good, good times!

For those looking for more, I strongly recommend the 1986 game Portal. It’s probably the first one in the genre and a thoroughly great game.