1991: Trade Wars 2002

Update: Find out more about the 50 Years of Text Games book and the revised final version of this article!

Trade Wars 2002

a.k.a. Trade Wars, TradeWars 2002, TW2002

by Gary and MaryAnn Martin (Martech Software)

later versions by John Pritchett; based on Trade Wars by Chris Sherrick

Released: June 1991

Language: Turbo Pascal 6.0

Platform: DOS / WWIVOpening Text:

What is your name? Zaphod Use ANSI graphics? Y

Initializing... Hello Zaphod, welcome to: Trade Wars 2002! (C) Copyright 1990,1991, Gary & Mary Ann Martin Brought to you by Martech Software, Inc (tm) Support BBSes (913) 832-0300 & (913) 832-0248 <Scanning for Hazardous Sectors you have marked to Avoid> No Sectors are currently being avoided. We haven't seen you in 4 days, welcome back. Searching for messages received since your last time on: No messages received. You have 100 turns this Stardate.

If you first got online after 1996 or so, you might never have connected to a BBS. If you first got online after 2006, you might never have even heard of one. Reading the histories of online games like dnd (1975) MUD (1980), or LambdaMOO (1990) can give the impression that gamers have been happily playing together on the internet since the 1970s, and in some special places like university campuses, they have been. But for most early computer users there was no cheap or easy way to connect to the nascent internet. For them, going online meant dialing into a local bulletin board system—and the games on those systems were a curious sort of multiplayer, because only one person could play them at a time.

Backing up: a BBS was simply a regular computer hooked up to a phone line, which anyone dialing in with a modem could control. Often this computer was just a spare in somebody’s home hooked up to a second landline. BBS host software let callers create accounts and provided access to whatever message boards, file archives, and games the system operator (sysop) had made available. Each BBS was its own tiny island, with unique user accounts, layout, information and entertainments. And since phone companies still charged by the minute for long-distance calls, most users called local numbers, exploring an archipelago of hometown systems via a notepad full of regular phone numbers, collected via word of mouth or found on other BBSes. At the peak of their popularity in the early 1990s, there may have been something like 150,000 such systems running.

While a large or commercial BBS might have multiple phone lines, most were hobby operations with just one, meaning only one person could connect at a time. So multiplayer BBS games had to be played sequentially, not simultaneously, like a board game with person after person taking a turn. Bandwidth over analog phone lines was slow, so all interactions were by necessity entirely text-based. 2400 baud was slow enough that downloading a single JPG might take ten minutes, but a few hundred characters of text could be transmitted each second, enough to fill a screen in a few moments. And that screen didn’t need to be drab: the ANSI text standard (which most computers by 1990 supported) allowed sixteen foreground and eight background colors as well as a range of special characters for lines, shapes, and textures—extended ASCII—which together could paint vibrant if blocky pseudo-graphics in an 80x24 grid of characters. While standalone games by the early ’90s had moved on to 256-color graphics and CD-ROM audio, BBS games were forced to attract players and hold their interest with nothing but their text. Their aesthetics were retro even in their prime: gameplay was the only place they could innovate.

Most of these games were standalone MS-DOS programs to which the BBS software could hand over execution, along with some metadata like the name of the logged-in user and their permissions. These were called “door games”: the user was in essence passing through an invisible portal between one program on the host’s system and the next. Since it was a standalone program, a door game could do almost anything a regular text-based DOS application could, not needing to conform to the limitations of particular BBS software beyond some basic hand-off details: earlier limitations around limited memory and compatibility had mostly been ironed out by the early 1990s. But to tell the story of how Trade Wars became the most popular BBS door game of all time, we need to go back even further, to a pair of games from the early 1970s: Star Trek and Star Trader.

We’ve previously covered Mike Mayfield’s Super Star Trek in this series. Star Trader (sometimes Traders) was another popular early BASIC game passed around and improved from one hacker to another, originating with People’s Computer Company member Dave Kaufman (whose Caves games probably influenced Hunt the Wumpus). Kaufman’s program took a very simple premise—buy low, sell high—and gave it a patina of sci-fi excitement by casting its players as interstellar merchants:

EACH OF YOU IS THE CAPTAIN OF TWO INTERSTELLAR TRADING SHIPS. YOU WILL TRAVEL FROM STAR SYSTEM TO STAR SYSTEM, BUYING AND SELLING MERCHANDISE. IF YOU DRIVE A GOOD BARGAIN YOU CAN MAKE LARGE PROFITS.

Multiple players sharing the same keyboard could take turns navigating a small region of half a dozen stars, looking for deals on goods like uranium, star gems, helium, and (naturally) computer software:

PLAYER 1, WHICH STAR WILL ARGOSY TRAVEL TO? QUIN THE ETA AT QUIN IS MAY 3, 2070 ARGOSY HAS LANDED ON QUIN $ ON BOARD: 5000 NET WT 25 UR MET HE MED SOFT GEMS 0 0 15 10 10 0 WE ARE BUYING: HE WE NEED 6 UNITS. HOW MANY ARE YOU SELLING? 6 WE OFFER $ 25900 WHAT DO YOU BID? 27000 WE OFFER $ 26100 WHAT DO YOU BID? 26500 WE'LL TAKE IT!

Star Trader was a surprisingly clever program for its day: the trading algorithm was smart, for instance, involving a hidden range of acceptable prices a merchant might take that would shrink the longer haggling continued. Also, it was fun to out-barter your friends, snatching up all the units of a rare commodity and watching your credits increase at their expense. Republished in the popular book What To Do After You Hit Return, it became an early computing standard.

Contemporaneously, Mayfield’s Star Trek also became a hit, merging the joys of exploring brave new worlds with the thrill of blowing up Klingons. Adding multiplayer to Trek became a popular hacker pastime. One variant called WAR cast one player as the Klingons and another at the same keyboard as the Federation; but WAR soon became DECWAR on the Digital Equipment Corporation’s PDP-10, which supported multiple simultaneous connections. DECWAR allowed up to ten players divided into two teams (Federation and Klingons) to face off in real time, and became wildly popular, evolving new multiplayer-specific mechanics and gameplay. When the first commercial internet providers began to appear, the multiplayer mainframe games were exactly the kinds of experiences they wanted to bring to home computer users: CompuServe re-skinned DECWAR as MegaWars (removing the Trek references and the original creators’ names) which became a popular part of the service for well over a decade.

But CompuServe then was expensive: $12/hour for access even at off-peak times. One of the many gamers who had heard about MegaWars but couldn’t afford to play was named Chris Sherrick, and he wanted to bring something like it to his free BBS. Based on second-hand knowledge of the game and his familiarity with the early BASIC classics like Star Trader, Trek, and Wumpus, in 1984 he debuted a game called Trade Wars and made it available for free to other sysops. In Sherrick’s game, players navigated a maze of sixty numbered sectors with complex interconnections (much like in Wumpus), buying and selling goods (as in Star Trader) while fighting off enemies and operating a starship with a range of advanced capabilities (as in Trek). It was a grab bag of successes from earlier games, put in a new package that anyone with a modem could dial in to play—no credit card required.

But Sherrick’s was not destined to become the most famous Trade Wars. After passing through a number of ports and revisions, a version of the game found itself in the hands of a Kansas coder and sysop named Gary Martin, who was trying to get it running on his BBS Castle Ravenloft (“the Loft,” as it was affectionately known). The software for the Loft couldn’t run a BASIC program as a door, so Martin was hunting for a working Pascal port. The best candidate he could find seemed buggy and kept crashing, so he decided to do some major surgery and add some tweaks of his own. After fits and starts of tinkering, he released his version of Sherrick’s game in 1986, under the name Trade Wars 2001. Martin’s version was at first quite similar to previous incarnations, with its main innovation to add some pop-culture sci-fi references (cribbing mostly from Star Trek and Star Wars) to lend it a bit of borrowed character. One of his changes was to name the game’s NPC villains the Ferrengi, who at the time were rumored to be the new big baddies in the upcoming Star Trek: The Next Generation show. Though the new TV villains would underwhelm and evolve into comic relief, they would stay the permanent antagonists in Martin’s game through decades of updates, grandfathered into ferociousness (and a now non-canon spelling).

Crucially, Martin also worked to make his version of Trade Wars compatible with WWIV, a new and more powerful BBS platform that would soon become one of the most popular in the country. In 1988, WWIV was rewritten in native C, which removed a limitation that had restricted door games to no more than 64K in size. With the room to make a much bigger game, Martin began a long-term revamping to make “the Trade Wars game that I wanted to play, not just a clone of what previous ones had been.” With the help of his new wife MaryAnn, who managed registrations and business affairs while also contributing ideas and designs to the project, the couple would in 1991 release Trade Wars 2002 (or TW2002), which would become the definitive BBS space trading game.

After launching TW2002 from your favorite BBS’s games menu, you’d give your character a name—either the same one you used on that BBS, or an alias if you wanted to play incognito—and claim your starter ship, perhaps a Merchant Cruiser with 20 cargo holds. You could then begin exploring a galaxy of hundreds or thousands of interconnected, numbered sectors: the exact count, along with many other details, could be customized by each sysop. The core game loop remained virtually unchanged from the days of Star Trader: dock at ports to buy and sell goods, warp between star systems, and try to turn your cargo into profit:

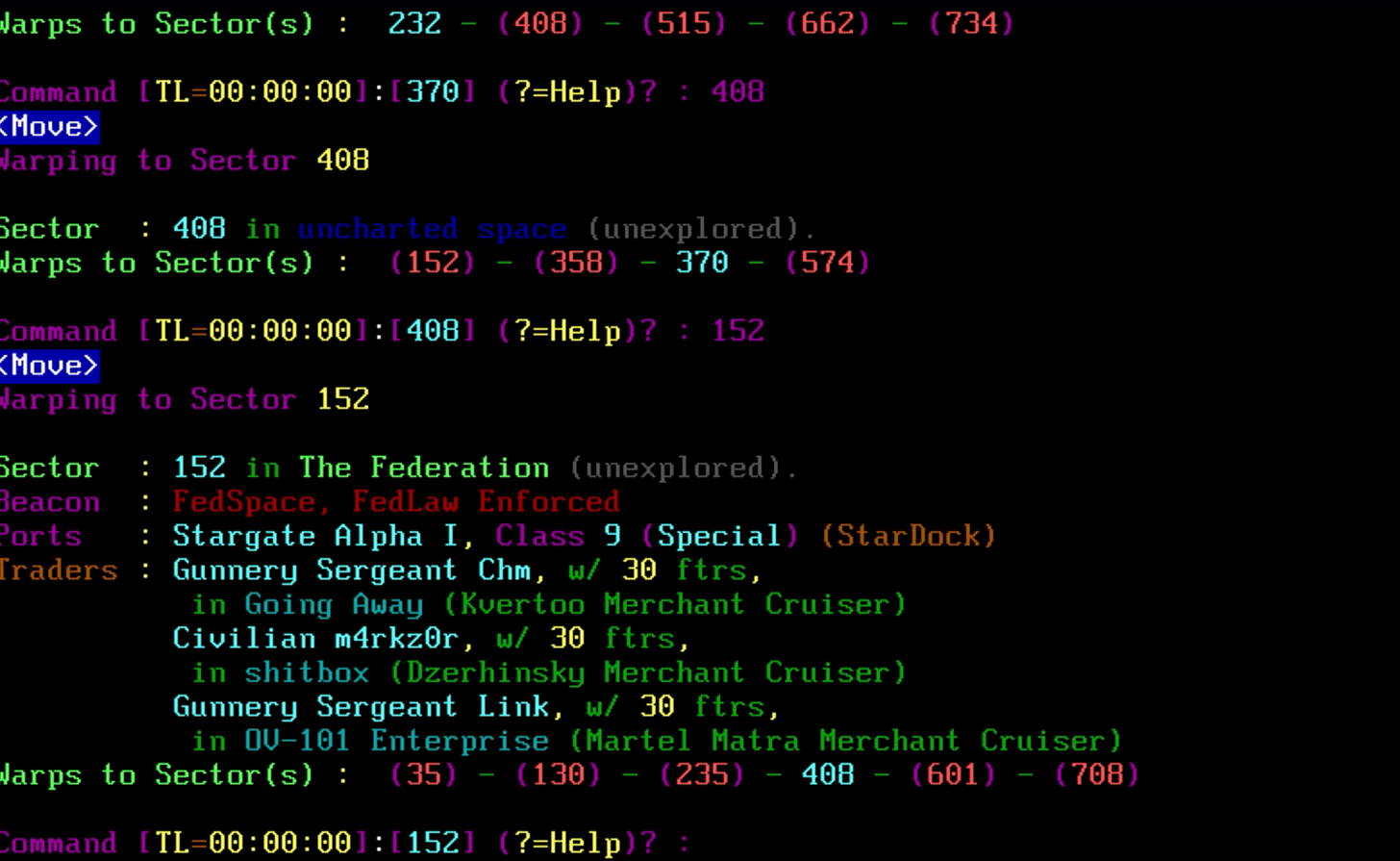

Sector : 885 in uncharted space (unexplored). Ferrengi: Sheccag Mioqtiap, with 8,000 ftrs, in Ovaoq Fadavej (Ferrengi Battle Cruiser) Warps to Sector(s): (383) - (707) Command [TL=00:27:51]:[885] (?=Help)? : 383 <Move> Warping to Sector 383 Sector : 383 in Tarterus (unexplored). Ports : Huygens, Class 2 (BSB) Traders : Civilian Ender, w/ 30 ftrs, in Sweet Justice (Impetuoso Merchant Cruiser) Warps to Sector(s): 885 - (249) - (273) - (279) - (620)

“Ender” here is another human player, offline along with all other players except the one who’s currently logged in. It’s also worth noting that while in 2021 the Substack platform does not support colored text, Trade Wars (like most door games) used it heavily to help players pick out key information as it scrolled by:

Command [TL=00:27:43]:[383] (?=Help)? : P <A> Attack this Port <T> Trade at this Port <Q> Quit, nevermind Enter your choice [T] ? T <Port> Docking... One turn deducted, 73 turns left.

Limited turn counts were a ubiquitous mechanic in door games to prevent overzealous players hogging a BBS’s phone line indefinitely; some sysops also enforced a real-world time limit, as the clock counting down after “Command” shows in the excerpts above.

Commerce report for Huygens: 09:55:10 PM Thu Apr 17, 2033 -=-=- Docking Log -=-=- No current ship docking log on file. For finding this neglected port you receive 50 experience point(s). You have been promoted to Staff Sergeant! Items Status Trading % of max OnBoard ----- ------ ------- -------- ------- Fuel Ore Buying 1710 100% 20 Organics Selling 1110 100% 0 Equipment Buying 830 100% 0

TW2002 used the same three core goods as had the original Trade Wars: Ore, Organics, and Equipment. It also used a bartering mechanic that had changed little since the 1970s Star Trader.

You have 220 credits and 0 empty cargo holds. We are buying up to 1710. You have 20 in your holds. How many holds of Fuel Ore do you want to sell [20]? 20 Agreed, 20 units. We'll buy them for 681 credits. Your offer [681] ? 720 We'll buy them for 687 credits. Your offer [687] ? 690 If only more honest traders would port here, we'll take them though. For your good trading you receive 1 experience point(s). You have 910 credits and 20 empty cargo holds.

In your first few days of play, a key challenge would be to find the StarDock, a major hub with useful services including stores, a shipyard, and sources of missions and interactions with other players. The StarDock was a key addition to Martin’s version of the game that went a long way toward making its galaxy feel more like a dynamic, living place. It’s filled with things to do: shop, gamble, visit a theatre to watch ASCII-art sci-fi parody “movies” (short animations) with titles like Vulcan Thunder. But more interesting are the chances for community interaction. The StarDock’s tavern provides a range of different ways to interact with fellow players: among other options, you can pay credits to post a public message that everyone will see, add to the graffiti scrawled on the bathroom wall, or pay a “grimy Trader” in the back room to learn information about other players, such as what sector their ship was last seen in. The grimy trader could share a huge selection of hints and useful info about the game state, provided you could think of the right things to ask him about and had the credits to pay:

"Why hello der matey! Have a sit and buy me an ale, eh?" You sit down and talk to the old Trader. (Enter the subject you want to know about, blank to exit) >FEDERATION "I can tell you something about FEDERATION, but its gonna cost ya!" "Would ye pay me 2,500 credits for it?" Yes "Tryin to cheat me eh? You bum! You ain't got the dough!"

The StarDock also holds secrets: the large menu of available commands doesn’t show all the options available. Pressing a key not listed on the menu would describe your character exploring the seedier, lesser-known parts of the station. A particular unlisted key would lead you to a locked door and a secret password which, once learned—from the grimy Trader, perhaps, or another player—admits you to the Underground, where nefarious players can buy illicit goods and coordinate against law-abiding Federation forces.

As you build up enough money to buy a better ship and properly equip it, a key challenge becomes finding a secure location to build a base. Planets could be created in any unoccupied sector by purchasing a Genesis Torpedo (a reference to ’80s classic Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan), and colonists could be taken from Terra in Sector 1 to the new planet to begin manufacturing goods. Planets could be defended with space mines or a Planetary Citadel, which could be built up with greater and greater defenses until, after weeks of daily turns, it became near-impregnable. An ideal sector for a home planet would be a dead-end, off the well-traveled routes around the StarDock or other key sectors, ideally in a lonely part of the map less likely to be stumbled upon by accident. Each game would require finding such a spot anew, since every BBS would have a different map configuration, randomly generated by the sysop with a program called BIGBANG.EXE before their version of the game went live.

Since combat could not be real-time, successfully attacking another player or their well-guarded base was mainly a matter of which side had the best equipment. While death was never permanent, logging on to find yourself floating in an escape pod, your fancy ship destroyed and your credits long gone, might form the basis of a long-term grudge that could take days or weeks of turns to repay.

Your fighters: 5,208 vs. theirs: 7,241 Choose your action, Captain : (F)lee, (A)ttack, (S)urrender, (I)nfo? F Constellation Attack! Combat computer reports damages of 738 battle points! You rush to an escape pod and abandon ship... Your Scout Marauder has been destroyed! Your trusty Escape Pod is functioning normally. For getting blown up you LOSE 99 experience point(s). Sector 130 will now be avoided in future navigation calculations.

Rivalries could be settled by putting a bounty on another player, or banding together with friends in a Corporation, which allowed for sharing goods and resources as well as access to better ships. The Martins were canny enough to realize this feature was less about promoting player cooperation than creating more chaos:

The whole point of the TW200x design was the underlying concept that “No one wins in a war”. When it comes down to fighting, both sides lose. It becomes a matter of who loses the most. The whole corporate design was there to stir the pot and cause more conflict amongst players, not to create safety in numbers.

Trade Wars has enough commands, ship types, upgrades, and strategies to support a wide variety of play styles: there are often multiple possible solutions to any emergent problem. For self-defense you might get a cloaking device to hide your ship, leave it in an out-of-the-way sector, or surround it with mines and booby-traps when you log off. You might earn credits by finding a good set of “trading pair” ports to shuttle goods between, by gambling, by fulfilling bounties on NPCs or other players, or by social-engineering your way into a Corporation before robbing them blind. Sysops were given back-end tools to customize dozens of details of a particular game’s configuration, from a player’s starting loadout to the number of sectors in the galaxy to the specs of available ships to how aggressive the Ferrengi would be or whether they were even called Ferrengi: this enabled each BBS to advertise their own unique flavor of the game. Evil-aligned characters could rob ports; good-aligned characters could gain access with effort to the Imperial Starship, a monstrously powerful ship capable of bombarding the hell out of evildoers. Every strategy had a counter-strategy and each play style had its strengths and weaknesses. Deeper than most door games, TW2002 spread fast and within a year was running on a huge percentage of BBSes. While exact data is impossible to come by—spread out over tens of thousands of individual systems—there may have been over a million regular players at the game’s peak, with more than 35,000 sysops having paid to register the game for their dozens or hundreds of users, and countless more pirated copies running on less scrupulous boards.

The Martins’ Trade Wars didn’t change much as time went on, beyond an irregular progression of bug fixes. John Pritchett joined the team in the second half of the 1990s to work on a version 3 of the game which would support simultaneous multiplayer: there were fewer BBSes by then and most of the survivors were larger operations with multiple phone lines. But BBS games were entering a rapid decline as more and more users dialed instead into services connecting them to the global internet—and increasingly over broadband, not dial-up, opening a new world of multiplayer gaming filled with graphics and low-latency action. Gary Martin had decided by the end of the decade that there was no point trying to compete:

You have to remember, this was back in a period where one developer could put out a complete game by himself. It didn’t take an art department, musicians, or celebrity voice actors to create a title. So in a world where all of these text BBS games are thriving, suddenly here comes a title like Wing Commander. Celebrity voice actors, a HUGE art department, coding department, music department, etc. The bar to create a competitive game was suddenly far too high to reach as an individual or even a small development company. Since I didn’t want to create an inferior game in that world, I chose to stop working on it entirely.

In 2000 Pritchett bought the Trade Wars IP from the Martins and took over maintaining their game entirely, creating versions that could be hosted over the internet and adding other small improvements. But the game was a harder sell in an always-online, global village kind of world. “It was the anticipation of the game that made it so addictive,” Pritchett later reflected. The tension of hearing a busy signal and wondering if someone else was messing up your shit; the camaraderie of a small community with usernames you recognized from other local boards and other local games; the feeling of handing off the universe from one player to the next, and knowing each time you connected you were the only person inside it; the surety that each player had the same fixed turn count, no matter how much or how little free time they had in real life—these experiences were hard to recapture on the web, superior though most everyone agreed it to be. Something ineffable had, nonetheless, been lost.

Door games, like play-by-mail games, MOOs, and others built around tentative ideas of what online communities might be, suffered a fate far worse than technological obsolescence when the very structure of community changed around them. Today they’ve been almost forgotten—almost. In 2021, there’s still a community of die-hard fans who run their own TW2002 servers and play their daily turns: booby-trapping ships with Corbomite Transducers as a nasty surprise for overnight attackers, saving up for an Interdictor Cruiser or Corellian Battleship, and posting gloating announcements in the tavern for friends and foe alike to see, next time they log in.

Trade Wars wasn’t trying to change the world: it didn’t boast a serious story or an innovative parser, and was more focused on perfecting what had come before than innovating anything new. But it was a lot of fun. It would be influential on designers of new generations of complex space games, like EVE Online or the X Series. The team behind Star Citizen, which crowdfunded hundreds of millions of dollars in the 2010s, cited TW2002 as one of their inspirations; so did the designers of early 2000s MMO Earth & Beyond. A spin-off called Dope Wars (replacing galactic sectors with downtrodden neighborhoods and Ferrengi with cops) evolved into one of the first popular browser games. And in 2009, PC World named the Martins’ game one of the ten best of all time for the platform. It was nice of them to remember the amateur text game that had drawn countless teens away from their CD-ROM drives, even if only for a while.

Next week: “Commend your souls, if butchers such as ye have gods. For now ye face the wrath of Silverwolf.”

The TradeWars Museum maintains a list of active TW2002 games, if you want to try finding a game with other people; you can also try running a server yourself locally via Windows Terminal or DOSBox. Thanks to the Museum and vintage guides from Psycho, Gypsy’s War Room, and Fred Wehner for game details and strategy insights, the Games of Fame blog and langesite.com for insights into the program’s genealogy, and Rick Mead and Josh Renaud for invaluable Gary Martin interviews. The Martins these days are really into elaborate Christmas light displays.

Fun article to read. I currently host The Official BBS Door Games & Apps Museum. It's a PCBoard BBS that has over 1350 door games installed and running. I have also cataloged these doors in a searchable database that can only be viewed by logging into the BBS via Telnet. For the best ansi emulation, use Netrunner Telnet Client to login. Danger Bay BBS -> dangerbaybbs.dyndns.org:1337

It was a lot of clean fun.... The imagination was stimulated. Wish I could get this going with my old friends again.