Update: Find out more about the 50 Years of Text Games book and the revised final version of this article!

Weyrwood

by Isabella Shaw

Published: November 29th, 2018 (Choice of Games)

Language: ChoiceScript

Platform: PC/Mac/Linux/Android/iOSOpening Text:

The heavy door to Messrs Holwood, Holwood, and Pende’s law firm closes firmly behind you, leaving you in the street.

In the morning light, the cobblestones reflect gold; the limestone buildings, neo-classical facades worn smooth by weather and mist from the Wood, shine a burnished silver.

Your lawyer was very congenial, very conciliatory, but all his counsel, all his well-turned phrases, and sympathetic manners revealed the same result: Prosper has confounded you again, with all its bizarre conventions and unique legal intricacies. Your fortune, paltry though it may be, is bound up in the property your guardian left to you.

One thing is certain: you need the money.

“Your favorite novel was probably written by one person,” Choice of Games co-founder Dan Fabulich notes,

but games are usually a collaboration between a lot of people: game designers, coders, music/sound engineers, illustrators, animators, QA, etc. There are a few superheroes who can do it all, but that’s exceedingly rare.

Even for those superheros, releasing a game on a major platform can be kryptonite. Managing contracts and partnerships, handling marketing and tech support, and jumping through the unique technical, financial, and logistical hoops of each storefront can be exhausting or impossible for solo creators. While the 2010s made it increasingly easy for non-technical designers to make text games with tools like Twine or ink, getting them in front of a mainstream audience remained as hard as ever—if not more so, with gamers increasingly directed to big hubs like Steam and less willing to trust download links from random websites. Fabulich’s company, Choice of Games, had hoped to change that: “to make it possible (indeed to make it easy) for one person to develop a full-length game, to write an interactive novel and make good money selling it online.”

Which explains how a new title debuting in 2018 on Steam, the App Store, and other major platforms could be the sole creation of a poet and opera singer who had never made a game before. A week before its release, rather than wrangling with Xcode or resizing screenshots she was onstage in Helsinki, singing the demanding title role in The Rape of Lucretia.

Isabella Shaw had always loved both writing and music, with a particular interest in older forms and neglected creators. In college she studied music and literature at Trinity College and Cambridge, with a focus on “medieval and early modern literature” and “12th century female mystics.” With a budding career as a talented mezzo-soprano, she was “dedicated to performing music by marginalized or unknown voices, particularly female composers throughout history.” While pursuing her passion for singing she continued to write, publishing a book of poems called Songs of Remembrance in 2016. She’d been familiar with choice-based text games through online portals that let players make and share their own, and had found parser games through internet searches for interactive fiction; but the idea to write a game of her own didn’t gel until she came across an announcement from Choice of Games that they were looking for writers. A story she’d been trying unsuccessfully to draft as a novella seemed like it might be a perfect fit for an interactive game.

Trace the story of Choice of Games back and you find, long before its founding, a curious text game called Alter Ego. Created by a psychologist and released by Activision in the days when big studios were still taking chances on weird, experimental titles, the game lets you choose your own path through the entire life of an average American woman or man—it was sold in separate gendered versions. Fabulich had been fascinated by it, and ported it to Java in the early 2000s, hoping more players might discover and enjoy it. He’d had plans to extend the game by adding new life paths not present in the original—single parenthood, homosexuality, more interesting professions—but the scope of such changes proved too daunting, and the game would remain running on his server in more or less its original form for years. (He also had plenty of other distractions: in 2001, he’d become a major player in the Cloudmaker community obsessed with solving proto-ARG The Beast.)

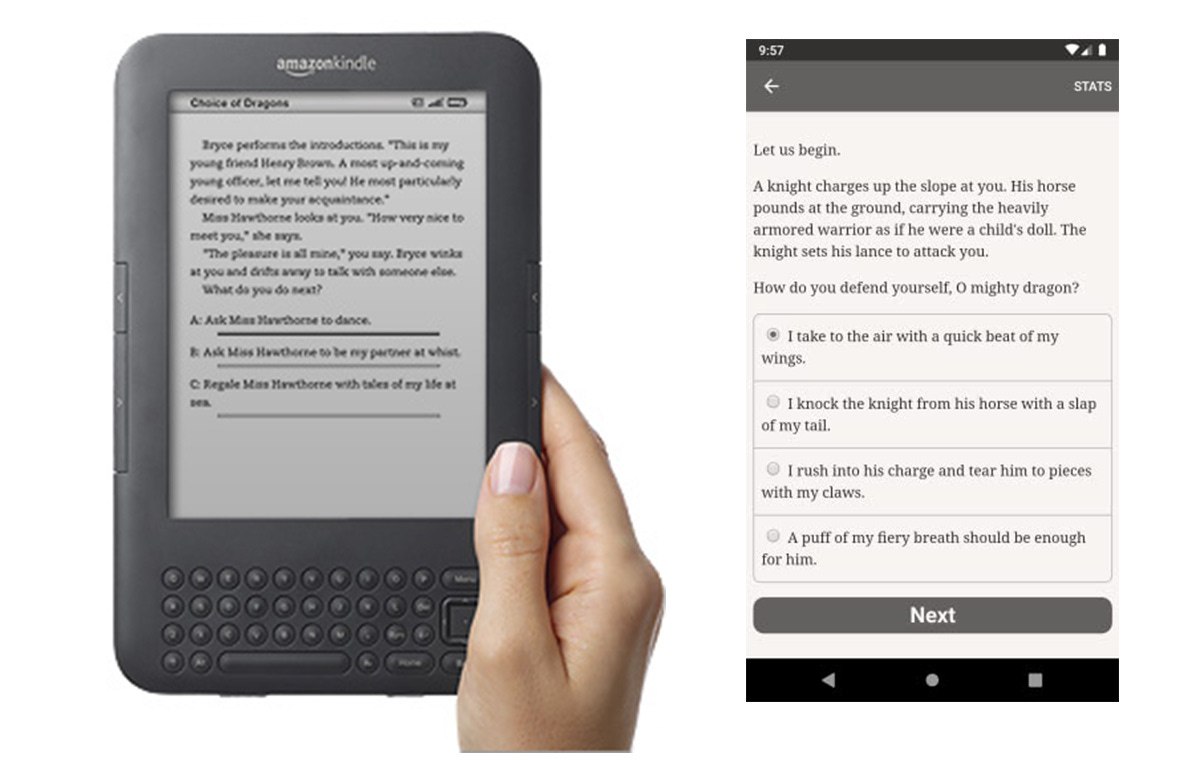

Sometime around 2008, Fabulich happened to check the server logs for his Alter Ego port and was astonished to discover it had been getting millions of pageviews a month, implying tens of thousands of people were playing. He wondered, twenty-five years after the rise of Choose Your Own Adventure, if gamebooks were having a generational retro moment. Many others were coming to similar realizations, along with the recognition that the rise of mobile offered new platforms and audiences for interactive books. Fabulich got together with a college buddy, Adam Strong-Morse, and in 2009 the two launched a trio of related ventures: a lighthearted game called Choice of the Dragon, a language called ChoiceScript they’d used to write it, and a company called Choice of Games to explore whether people might be willing to pay for digital gamebooks.

Dragon used much the same formula as Alter Ego, except that instead of making choices to decide what kind of person you would be, this time you were choosing what sort of dragon:

A knight charges up the slope at you. His horse pounds at the ground, carrying the heavily armored warrior as if he were a child’s doll. The knight sets his lance to attack you.

How do you defend yourself, O mighty dragon?

* I take to the air with a quick beat of my wings.

* I knock the knight from his horse with a slap of my tail.

* I rush into his charge and tear him to pieces with my claws.

* A puff of my fiery breath should be enough for him.

Despite eschewing graphics or a visual UI for a deliberately simple interface styled like an ebook reader, Dragon too proved wildly popular, with the free game eventually attracting more than a million downloads. Soon Choice of Games began releasing commercial follow-ups, originally under brand-aligned titles like Choice Of Broadsides or Choice of the Vampire. Building up an audience through a mailing list of fans—and promoting their titles more to readers than gamers, since their software could run on more text-centric devices like Amazon’s early Kindles—the company soon found itself consistently in the black. Their games, as a recurring line in their promo materials proudly stated, were “entirely text-based—without graphics or sound effects—and fueled by the vast, unstoppable power of your imagination.” People bought them. Soon the company was releasing a dozen or more titles per year, branching out into many different genres while honing a consistent house style that focused on exciting adventure, romantic subplots, and a constant rhythm of interesting decisions.

As its name made clear, the company’s goal was to make choosing the foundation of their stories:

Many games work by surrounding interesting choices with lots of tactical play or interactions with a set of game systems. That can be fun, but it means that relatively little of the playing experience is about making choices at a high-level. In contrast, by creating a game system that is all about multiple-choice interactions, we can focus on the choices we find interesting—moral choices, trade-offs between different values and characteristics, and so forth. When you play one of our games, you should be making meaningful choices all the time.

While Choices and Lifeline used decision points mostly to create a compelling sense of personal connection, Choice of Games was interested in how both the act of choosing but also the results of a choice might impact a narrative experience. To enable meaningful consequence without a combinatorial explosion of branching paths, the company uses an approach they call “delayed branching.” ChoiceScript games are driven by a set of story-specific number variables which individual choice points might change. As the story progresses, key moments will hinge on these stats more often than individual choices: as if “the decisions you’re making [across the game] are sort of taking a vote about what will happen next” (source). Rather than dozens of wrong choices for each correct path (leading to the dreaded “You Have Died” endings of classic gamebooks), or an ongoing story told from a pool of reusable content as in games made with StoryNexus, Choice of Games wanted each playthrough to tell a satisfying and finite story with a beginning, middle, and end. The core design decision for a ChoiceScript game, then, would be devising the set of stats—the “memory” of each particular story—that best let players explore how their character fit into its overall dramatic arc. And rather than focus on a single axis of choice like “good versus evil”—where the player tends to make a single decision early on and keep confirming it throughout—a range of interesting stats gave authors continuous opportunities to pit them against each other, forcing the reader to keep asking questions about what kind of protagonist they wanted to play.

Most of the stats tracked by Weyrwood relate to your character’s social reputation: are you respectable or scandalous, principled or manipulative, influential or withdrawn? This was appropriate for a game described as “a Regency fantasy of manners, daring, and magic.” The story centers around a town called Prosper, part of a fantastical world where humans and magical creatures live alongside each other—not always easily. Built at the edge of the Wood and the dangerous Wilds, the town receives magical protection through an ancient three-party contract signed by its human founders, the capricious Weyrs of the forest, and the scheming daemons of the Wild.

But the cost of safety is high. Each landowner holds a currency called spina: magic thorns bound to the bearer’s soul. Acting in tune with the social rules of Prosper, or exerting your will to become respected and influential there, gains you spina as well as social clout. But behaving shamefully, transgressively, or with weakness causes your spina to drain away. If you lose them all, you Fall—meaning a daemon can come to claim your soul and turn you into one of their mindless thralls.

There’s a commotion at the far end of the hall. A distinct, yet undefinable, quality of air is streaming into the room, and it makes your nostrils sting. It’s not exactly sulfur, nor is it iron, nor is it camphor, but a sort of memory of those scents, along with something else bitter and pungent.

A rending sound like the scraping of metal on bone makes the hair on your neck stand on end.

Someone—stumbling down from the games room—has just lost all their spina, it would appear. A pale circle is blossoming around the unfortunate gentleman, and a chill not wholly natural descends. ...One woman—apparently the unfortunate’s relation—turns green-faced and slides towards the floor; those standing nearby barely catch her.

...A slice of shadow appears in the summon-circle; a daemon, point-chinned and elegantly turned out in a sweeping frock coat of bright vermilion, appears, as if walking from a long way away.

...This is an immutable part of the Rules, and the consequences for interfering with the Falling itself are severe indeed. ...Nevertheless, you are stirred to action.

* I grab hold of the victim’s arm to stop him from being carried away.

* I console the lady by telling her that this is an act of justice.

* I offer the lady help.

* I offer the daemon one of my own spina.

As the game begins, you the player—raised in Prosper but departed long since for the City—have returned to claim an old inheritance. Though you had thought the town and its dangerous rules behind you, on arrival you find a small purse with your long-forgotten spina waiting for you, the magic of the inescapable contract still binding your soul.

While your spina remains so low, you are vulnerable.

The Rules are there to protect you, supposedly. Unfortunately, they can be volatile, relying on the intricate web of secrets that Prosper’s founders, the first Gentry, wove. Manners are of the essence, and a false move can send you plummeting down.

...[You have] nine spina... Nine chances to go wrong. Nine chances to prove you know your worth and make your place in Society.

“As a pre-teen and teen, I ingested quite a lot of 18th and 19th century literature,” Isabella Shaw recalls: “Jane Austen, yes, but also Fanny Burney, Maria Edgeworth, the Bronte sisters, Wilkie Collins, George Eliot, Elizabeth Gaskell...” The premise of the game came to her full-formed in a dream, but its logic made sense to her waking mind the more she thought it over. “I think there is something about a setting that requires strict social rules that seems [to] graft nicely with the threat of wild magic,” she reflects:

of otherworldly rules that can align with and brush against these social requirements. Social rules in many ways can have a ritualistic, weighted meaning—something subtle might have been said or done that has a dramatic effect upon a person’s status or possibilities. This kind of subtlety and weighted consequence already can feel like magic—invisible currents, running through a room or situation, that can cause dramatic shifts in story.

While spina provides a conceit for exploring issues of class division and economic divides, in Shaw’s world these are divorced from the prejudices of gender, sexuality, or skin color in our own. The gossips in Prosper will whisper if you run low on spina or show up to a dance dressed like a slob, but won’t care if you’re a man in a corset, or arrive with another man on your arm. NPCs are described with a range of skin tones, subtly puncturing the default whiteness of much fantasy or period literature (where, as with text games, both thoughtless and well-intended decisions not to mention race can flirt with erasure). Prosper has brutal social rules, but they’re a deliberate subset of our own, letting the author apply both escapist fun and social commentary in selective strokes.

“This game does an excellent job of showing that wars are fought and won in a conversation as often as a sword fight,” one reviewer noted. Managing alliances and rivalries is critical to achieving your goals, and you’ll have decide who to traffic with and who to trust—both among the people of Prosper and the daemons and weyrs outside, who offer rare but dangerous chances to increase your spina:

He is a Weyr—however hostile—and there is a pattern laid out here, and a system of courtesy. If you ask to bargain, he cannot harm you without breaking the contract...

* Try to bargain [click]

* Run away.

* Attack [him].

* Refuse to bargain.

“I would make a bargain,” you say, as persuasively as you can.

The Weyr stops short; his lantern-like eyes narrow slightly, just once...

“Humans are too conniving,” he says finally. “They are too glib by half, though not nearly as clever as they think. Give up half your silver tongue, half of your daemoncursed ability to weave knots of treachery, and you shall go free. And receive spina, for that is what you always crave.”

He is asking you to give up your ability to lie. It strikes you with a near-physical blow, the cost. You knew it would be steep, but so steep...

* “I’ll do it.” [click]

* “Take my principles instead.”

* “Take my empathy instead.”

* “Take my subtlety instead.”

* “Take my boldness instead.”

...“Very well,” the Weyr says. The spina settles into your skin with a ripple; you shiver.

And the wood wraps its arms closer around your heart.

As the game progresses and the true nature of the founders’ contract becomes clear—daemons, naturally, love a good loophole—you’ll have to decide whether Prosper is a place worth fighting to save and make once again your home, and where and to whom your own allegiances lie.

One of the key values the Choice of Games founders had brought to their company was a sense of social responsibility, which manifested in the ways they treated both their characters and their writers. Jason Hill, who joined the company shortly after the release of Dragon (and had been friends with Fabulich since “the first day of eighth grade”), noted that a core principle of the company was “trying to be as egalitarian as possible, so that anybody can find themselves in the story.” Rather than leave representation up to writers to include—or not—the founders decided every game they published would let players choose their gender and sexuality. In 2010 queer representation in games was still rare and it was still noteworthy for a game to offer same-sex romance options. The company encouraged authors to give their players even more opportunities for expression, too. In Weyrwood you don’t make binary choices about gender or sexuality: rather, a series of decisions let you play a character, for instance, whose gender identity has evolved over time; or who presents themselves differently than how they feel inside; or who wants only friendship, not romance, with Prosper’s marriageable residents. Choice of Games also differed from many competitors in sticking to a traditional up-front pricing model, rather than using in-game currencies or premium choices. If you bought one of their stories, you bought the whole thing, something many players appreciated.

The company strove to treat its authors equitably as well. Rather than originating ideas in-house and hiring contract writers to execute them, the company has come to operate more like a traditional publishing house, with authors pitching ideas, receiving editorial support, and maintaining control over their intellectual property and storytelling. Weyrwood, like most Choice of Games titles, was developed over a period of more than a year, working its way through a pipeline that had been refined across dozens of authors and releases. Initial pitches would be workshopped with the author to hone in on the right set of stats that captured the story’s themes and allowed for interesting decisions for the player. A full outline of chapters and major choices would be agreed upon before writing began. Authors worked directly in ChoiceScript, with technical help available for those who needed it. The language had been designed to stay simple and accessible, as part of the code for a choice point in Dragon demonstrates:

How do you defend yourself, O mighty dragon?

*choice

#I knock the knight from his horse with a slap of my tail.

You swing your mighty tail around and knock the knight flying. While he struggles to stand, you break his horse's back and begin devouring it.

*set cunning %+10

*goto VictoryStats could be checked to alter story text or choices, or adjusted with a method called “fairmath” which ensured they remained within the expected bounds of 0 to 100. The line *set cunning %+10 might increase cunning by a significant amount were it set to 50, but only by one or two points at 90 (and by none at all if already maxed out). This let authors focus on the relative effects of choices while the system handled math and edge cases. Other variables might track anything from names to pronouns to counters, modifying text inline as appropriate or changing what options were available to choose. Some Choice of Games titles could become enormously complex with their assembled text, taking pages to conditionally assemble a single customized paragraph when such power was needed.

An editor assigned to each project—a rare luxury for an indie game writer—would review chapter submissions incrementally as they arrived: both for typical editorial concerns like unclear writing or grammar errors, but also with an eye to ensuring a steady pace of frequent and interesting decisions. A core design philosophy, company editor Rebecca Slitt noted,

is that there are no “right” or “wrong” options. Rather, all options should be equally interesting, and even if the character fails to achieve their goal, the failure should be just as interesting as the success. So we have to make sure that no path through the story is easier or harder than the others, and that no option gives disproportionate benefits or penalties.

After the editorial phase came several rounds of testing to catch bugs and further improve the story. A ChoiceScript test suite could find errors where a story got into an infinite loop or petered out unexpectedly; another feature could play through thousands of times and highlight passages rarely or never seen, indicating perhaps a design or technical mistake. Finally the game would move into marketing and distribution, where cover art would be commissioned, trailers edited together, and launches scheduled on major mobile and desktop platforms: the company handled all these concerns for their authors in exchange for their cut of the profits (and a smaller one than traditional book publishers tended to take). By 2018 Choice of Games had released over a hundred interactive novels through this pipeline, learning through constant feedback from their players what worked and didn’t, and refining their style of choice-based storytelling into a consistently successful formula. In 2018 alone they released eighteen other titles besides Weyrwood—not counting those released through a separate label, Hosted Games, which let authors publish ChoiceScript stories with less editorial oversight and fewer restrictions on style or structure.

From an unlikely beginning with a port of a forgotten experiment, Choice Of Games has now grown into a sustainable success story that’s lasted for over a decade, a slow but steadily visible presence for text-only games. In 2014 the company published the first pure-text game ever to appear on Steam. The following year, they successfully lobbied to become a qualifying publisher for SFWA, the Science Fiction & Fantasy Writers of America, granting access to a useful professional organization for their authors. The SFWA runs the Nebula Awards, which in 2019 created a Game Writing category: a number of Choices of Games titles have been nominated in the years since. The company has mentored (and provided a paycheck for) dozens of emerging interactive narrative authors, many of whom have gone on, or returned, to careers in the mainstream games industry. And it’s become much more common for games to include a wider range of identities than the straight white dudes so common as game protagonists of earlier decades. The company continues to remain progressive: their newer titles now commonly offer paths for poly, ace, trans, or nonbinary heroes, too. “One of the things that I’ve been really proud of,” Fabulich notes, “is the ability to say, yes, everybody can be involved... you can play these games, you can write these games, you can be part of the broader gaming community.”

Since Weyrwood, Isabella Shaw has kept pursuing a career as a musician: in 2021 she had an active schedule singing roles by a range of composers both classic and modern. She has also kept writing—in 2020 she published another book of poems, Wilderness, accompanied by original harp music—but she hasn’t released another game. And that’s okay. Writing interactive stories was once the sole domain of those who’d devoted a major chunk of their lives to learning how. Interactive fiction fans now get to enjoy new kinds of playable stories—the ones written by everyone else.

Next week: Text games return to their roots, but this time entwined with the infinite grafts of a strange, brand new technology…

You can try the first few chapters of Weyrwood free online and purchase the rest of the story for various mobile and desktop platforms. The latest from Choice of Games can be found on their website, as can details about ChoiceScript, which is free to use; there’s also a ChoiceScript version of the original Alter Ego port. Isabella Shaw is online at isabellashaw.eu.

Disclosure: I have previously written for Choice of Games. As of this writing I am not receiving any ongoing royalties or other financial consideration from the company.

Great article! I really liked how you stepped us through the history of Choice of Games itself.

Interesting. On the topic of opera singers / game designers, there is also Shadi Torbey (https://www.boardgamegeek.com/boardgamedesigner/37729/shadi-torbey), although he designs board games and not video games. I wonder if there are any others.