Update: Find out more about the 50 Years of Text Games book!

What’s the first text game with a “transcript” (back-and-forth natural language interaction between a human and computer)? The answer may surprise you, because back-and-forth interactions were not how early computers were designed to work.

Many game history texts mention an unspecified number of 1950s “business management games,” often cited as some of the earliest text games. Period sources do discuss dozens of these games, but it seems there were really only two that were prime influences.

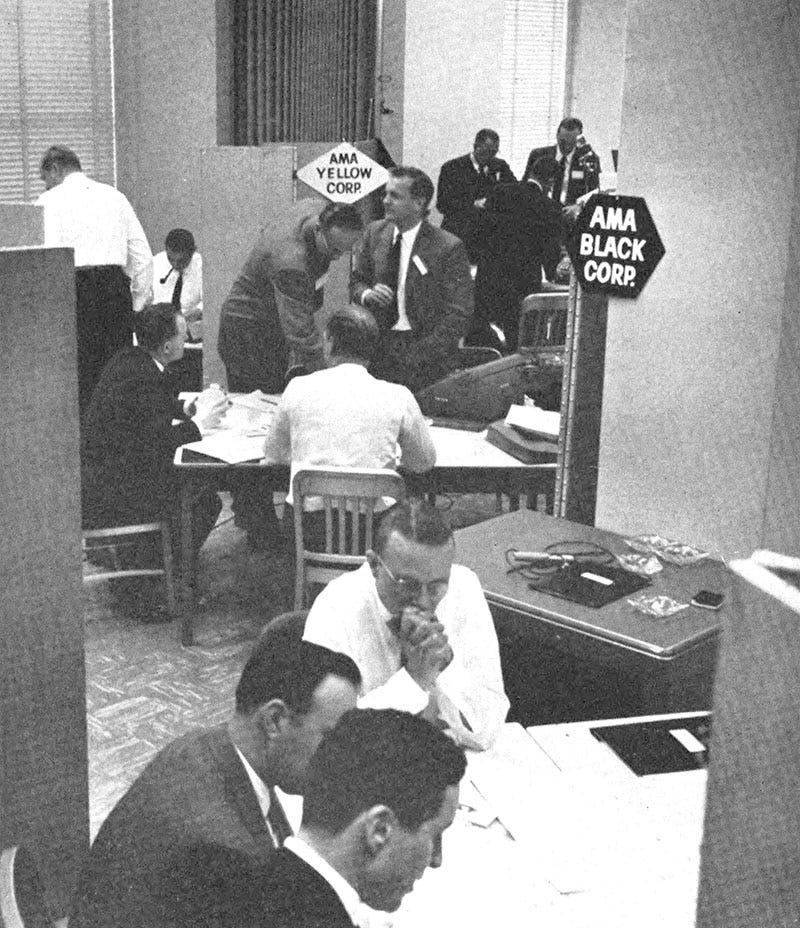

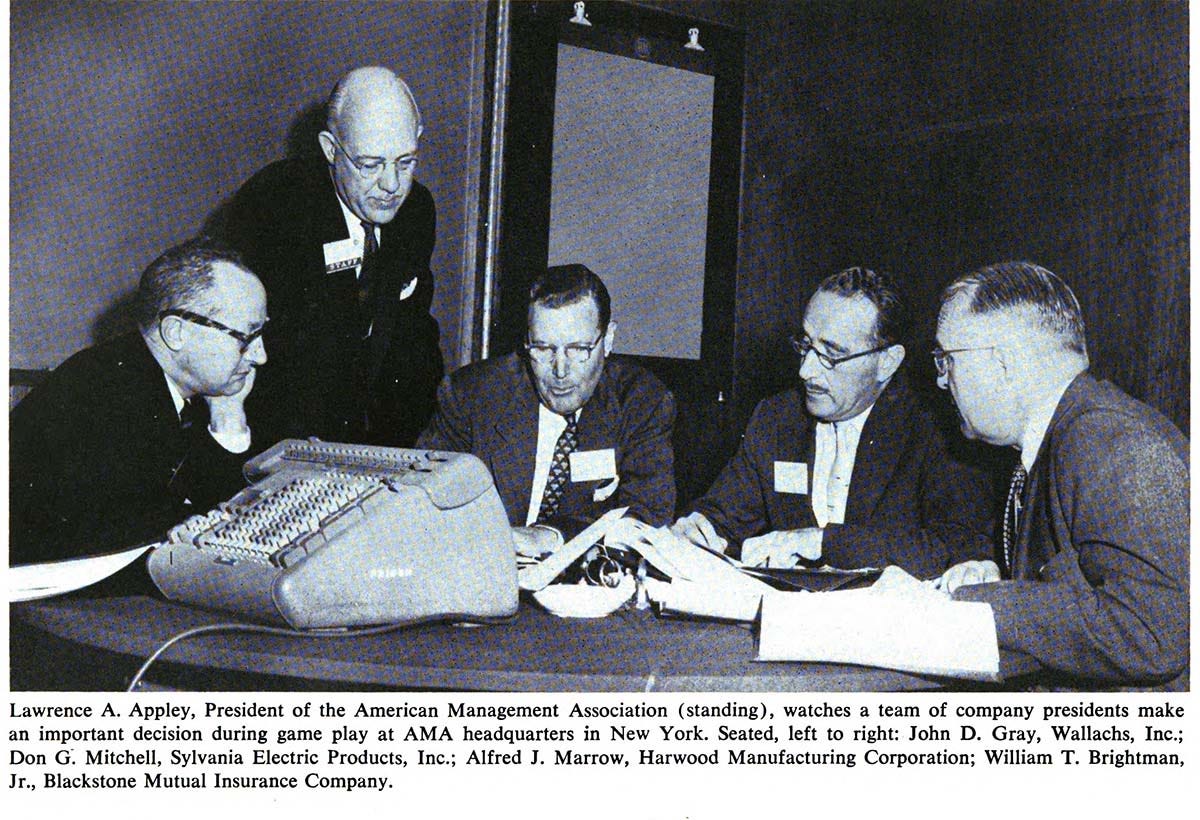

The first was designed by the American Management Association, and originally debuted at an exclusive (and probably expensive) retreat for business executives in July 1957. It was called “Top Management Decision Simulation” (sometimes “AMA’s Top…”), credited to Franc M. Ricciardi, Clifford J. Craft, and a half-dozen others, and was a relatively simple demonstration for its niche audience. The executives were split into teams, each controlling a virtual firm manufacturing a single product. They could set a retail price and divide expenditures between five possible categories, including rate of production and a marketing budget.

An IBM 650 mainframe would run each team's decisions against a simple economic model and churn out quarterly reports. In trying to track down what the actual input/output for this game looked like, though, I discovered something interesting.

(A note: the game is described in depth in many papers and in a book published by AMA in 1957, which might be the first full-length book ever written about a computer game. It’s available online here. The book notes the AMA game was directly inspired by the firm's research into early computerized military wargames, which I wrote about earlier. What AMA designed was, in essence, a business wargame: another example of how much, for better and worse, the military influenced early computer games.)

Anyway: few people were experienced in operating computers in 1957, and practically zero senior business executives. How, then, were they taught to play a computer game in the span of a weekend retreat? Of course, they weren't, despite the presence of a high-tech device in this promo shot.

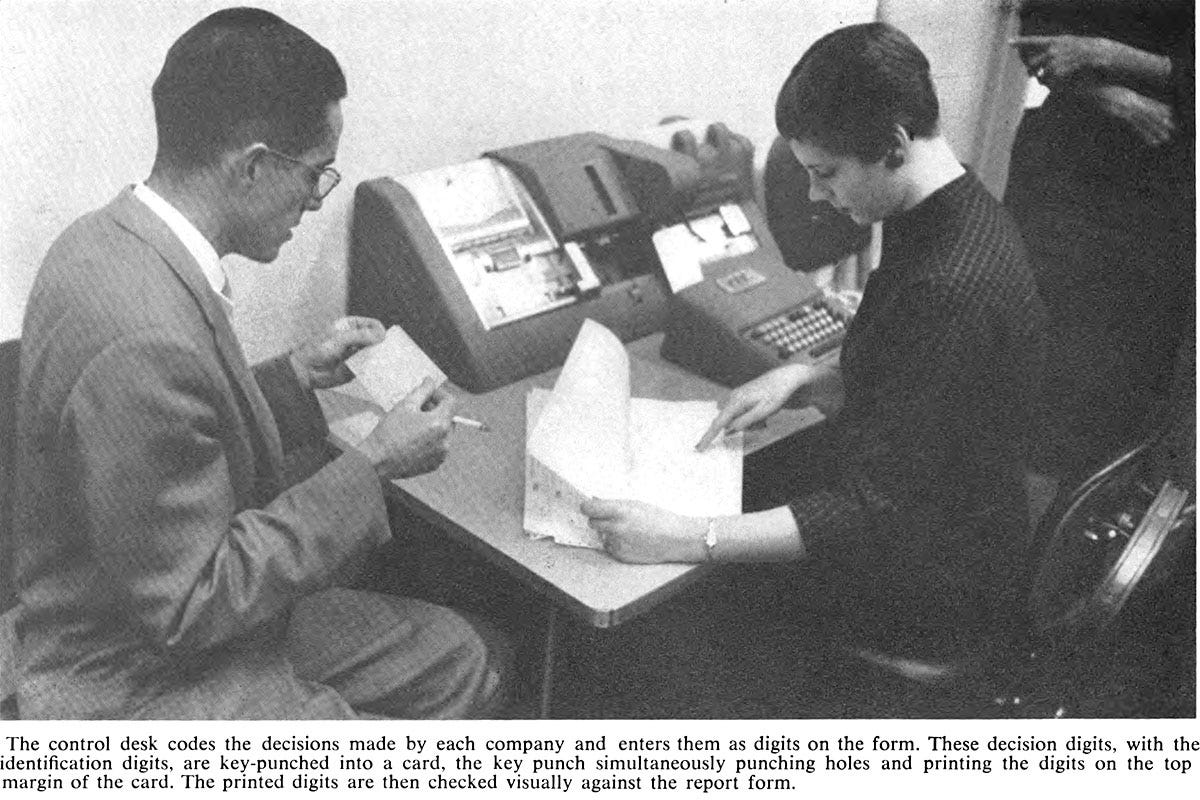

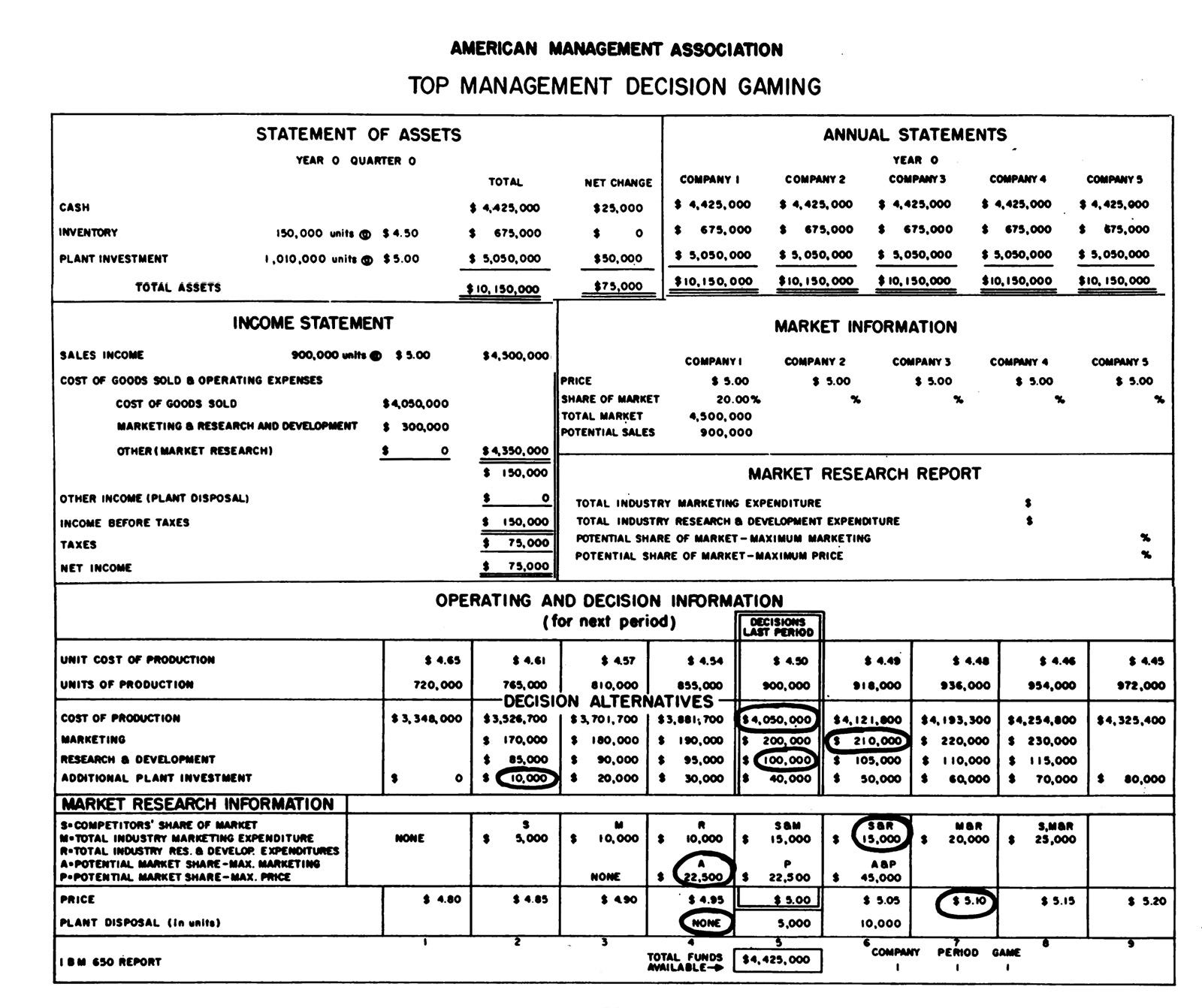

Each team got a printout summarizing the result of the previous turn (one fiscal quarter). It also had a list of “decision alternatives” for the five numbers they could tweak each turn (like their product’s retail price): four higher and four lower than the current value in ~5% increments. The execs would circle each decision alternative they liked on the worksheet and hand it to an operator, who'd convert it to a properly formatted punch card for the computer. (Love how the upper management men are circling numbers and a competent operator is running the equipment.)

Here's a pic of a full worksheet, with the previous results on top and circled decision alternative on the bottom. It's not clear from the book, but I suspect this was re-typeset for publication to look nicer than the actual sheets.

The program's output each turn (27 punch cards per company) would be sent via a separate program to an IBM 407 printer, which would print the numeric results on what were probably pre-printed blank worksheets. Teams had 25 minutes to make decisions in the first few rounds, which was later shortened to 10 minutes: this was possible because, sheer novelty aside, the game was so simple. But it inspired a vastly more complex game which would become highly influential.

A group of faculty members at Carnegie Tech's Graduate School of Industrial Information heard about the AMA game, and thought they could do something much more sophisticated. They wanted a game complex enough to be played by teams of grad students over an entire semester. Their game (first played by faculty in summer 1959 and by students that fall term) was vastly more complex, with over 1000 variables related to each fictional company and over 300 possible decisions. This game also used worksheets and reports printed on templates, but used far more of them.

This game is also described in a book, by the way: “The Carnegie Tech Management Game: An Experiment In Business Education” (1964). As far as I know it's not available online, but I managed to acquire a physical copy, which the remaining scans in this thread are from. This game (credited to Kalman Cohen, Richard Cyert, and William Dill) is also sometimes just called “The Management Game,” which speaks to how influential it became in this area.

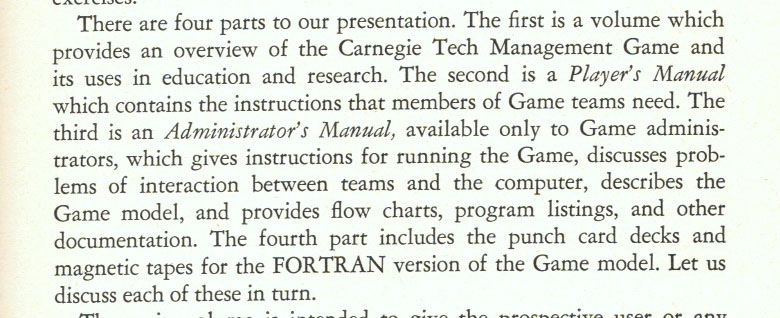

The book unfortunately doesn't specific implementation details, which were published in a separate “Administator's Manual” which I haven't been able to find. Note, though, the distinction between a “Player's Manual” and secret “Administrator's Manual,” a decade and change before D&D!

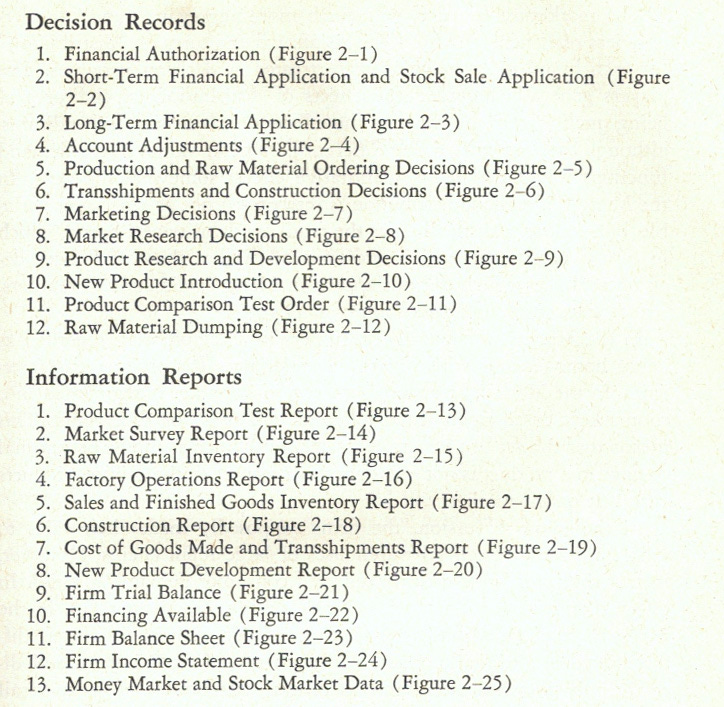

In Carnegie's game, each team of 5-10 students could submit up to 12 unique “Decision Record” forms each turn describing their business decisions in some depth: everything from factory construction to bank loans to raw material orders and R&D budgets. In return, they'd get back up to 13 unique “information reports” detailing the results of their actions. You might think of each of these 25 forms as like a single UI screen in a modern strategy game, indicating the depth of complexity here.

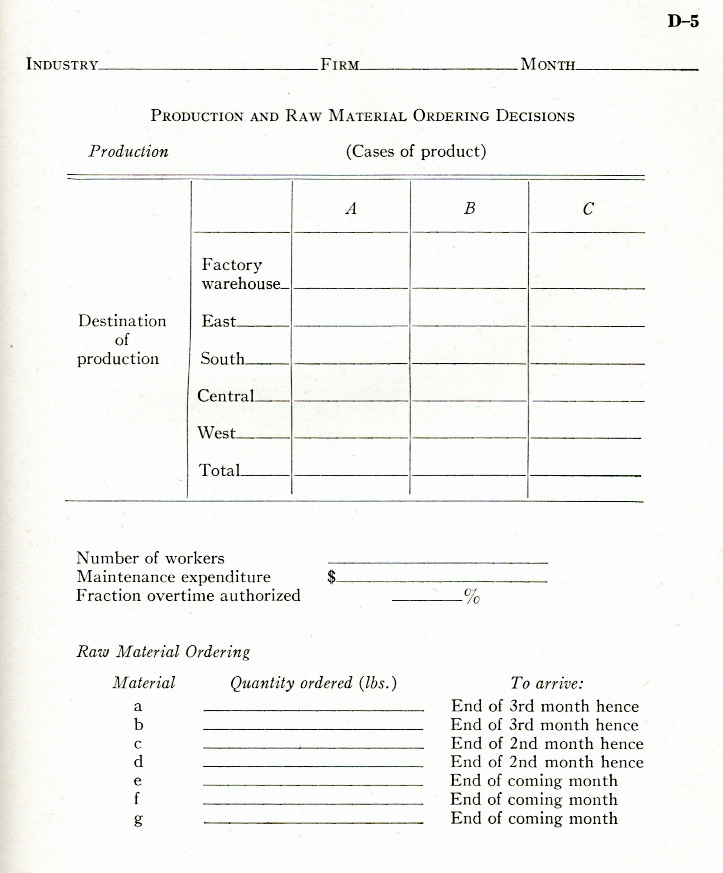

Here's one of the Decision Records, for ordering raw materials to manufacture products. Again, players would fill this out in pen or pencil & hand it in to “a clerk in the statistical laboratory” who'd convert it to keypunched cards.

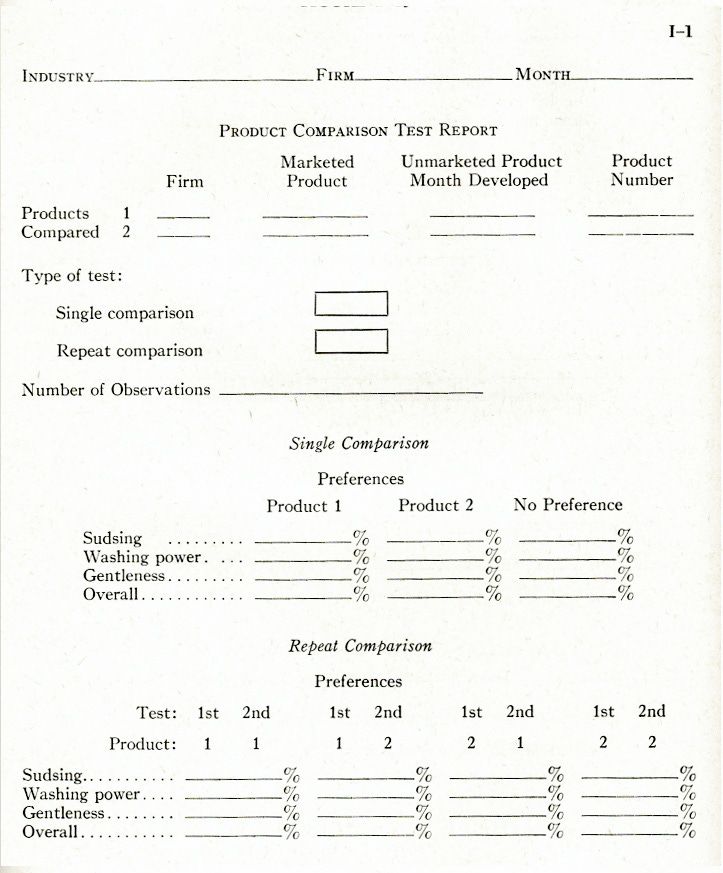

And here's a sample blank Information Report, showing the results of market research. The game was designed specifically around companies selling detergent, in part because one of the faculty members who created it had previous experience in that industry... and, ironically, because it was a field seen as relatively immune to the expanding technological changes disrupting so many other industries.

So this gets back to my opening point about looking for early transcripts. In these games, there really aren't any: because a transcript is linear, and that's not the way players were interacting with these programs! Instead, you'd submit some number of input forms and get back some number of output printouts. They weren't "ordered" in any particular way: they were just different windows into the state of the running simulation. "Transcripts" had to wait for the linearity of a command prompt!

Carnegie's game proved successful and was widely copied: the vast majority of the dozens of other business management games of the late 50s and 60s are direct clones or remakes. By 1961, there were over 100 of these games running at business schools. These kinds of asynchronous, batch-processed games mostly died out with real-time interactive computers, but survived in various forms like play-by-mail (see my coverage of Monster Island): which, like Carnegie's business wargame, could get wildly complicated.

So, what IS the earliest text game with a transcript? Computers were typing text out to people as early as the 1940s—Christopher Strachey had a checkers program that used its teletype to trash talk the player in 1952!—but processing text typed back was harder. One early candidate is a 1959 chatbot program called “The Conversation Machine,” designed to chat about the weather. There are a lot of other potential claimants to this throne, though, depending on your exact definitions. We'll have to save it for another post!

There's more original research on the early business simulation games and lots more fascinating computer game history in the 50 Years of Text Games book!

You may not know of one of the earliest books on how to design and use these games - Management Games, by Joel Kibbee, Clifford J. Craft and Burt Nanus, Reinhold Publishing company, 1961. It was based on work at Remington Rand UNIVAC Division.

I played one form of this game as a senior at Clarkson College of Technology (now Clarkson University) in 1966. You might try their library (if it still exists) or the Business Department for an admistrators manual.