The Gostak

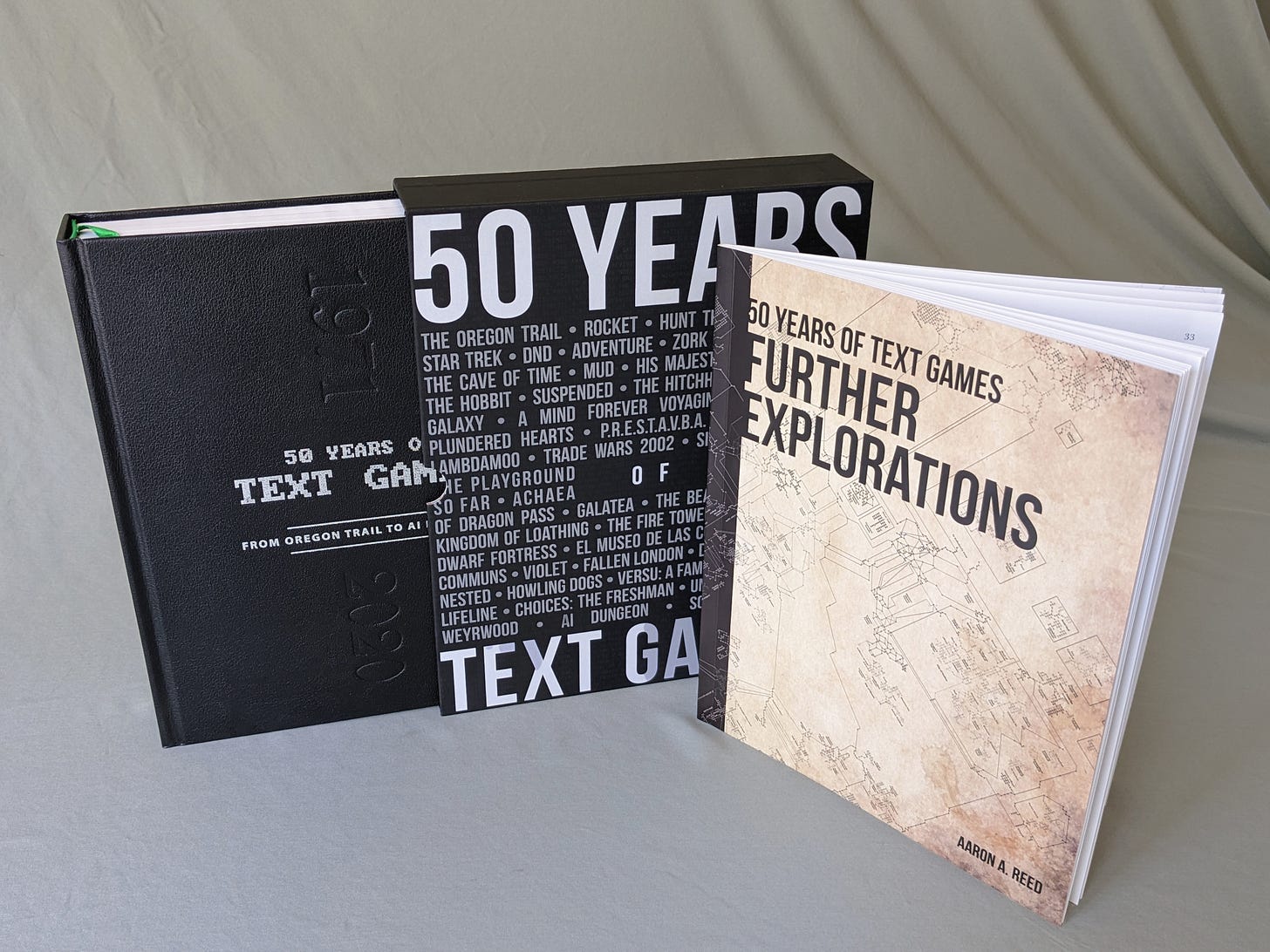

It’s been a while since I’ve posted a new article, but I’m bringing the blog back (albeit at a somewhat slower pace) to celebrate the impending launch of the 50 Years of Text Games book. Books, actually: the Collector’s Edition comes with a bonus booklet, “Further Explorations,” featuring some of my favorite games and genres that got left out of the main series. I’m happy today to debut a chapter from “Further Explorations” about one of my favorite interactive fiction games of all time. Enjoy!

The Gostak

by Carl Muckenhoupt

Released: Sep 30, 2001 (in IF Comp)

Language: Inform 6

Platform: Z-machine v5Opening Text:

Finally, here you are. At the delcot of tondam, where doshes deave. But the doshery lutt is crenned with glauds.

Glauds! How rorm it would be to pell back to the bewl and distunk them, distunk the whole delcot, let the drokes discren them.

But you are the gostak. The gostak distims the doshes. And no glaud will vorl them from you.

Note: this article contains spoilers for The Gostak.

The words of most interactive fiction provide a porous interface to the world beneath: as in most linear fiction, clear windows that plainly reveal the story they narrate. But try to play a game (or read a book) written in an unfamiliar language, and the world beyond goes dark, symbols awkwardly imposed between you and their signifiers. In an interactive work, this prevents not only understanding but progress: if you can’t learn what to type to make the story continue, you’ll never even see the words beyond the opening scene. This is more than a matter of vocabulary. Without familiar linguistic structures, we’re helpless to distinguish verbs from nouns, past tense from present, articles from pronouns. But this begs an intriguing question. In an interactive work, how much of the struggle to operate it comes from meaning, and how much from syntax? With familiar linguistic rules, could you learn to play a text adventure whose nouns, verbs, and adjectives were utterly unfamiliar?

Carl Muckenhoupt had wondered for years before he wrote The Gostak whether you could create a game about “learning to function in a world you have no basis for imagining.” Reading nonsense prose was one thing—you can enjoy a poem like “Jabberwocky” even with no idea what it means for slithy toves to gyre and gimble—but for an IF player to actually use verbs like gyre or gimble to act upon a simulated world seemed a rather more difficult problem.

Then he came across an old linguistics chestnut first popularized in the 1923 book The Meaning of Meaning, involving the seemingly nonsensical sentence “The gostak distims the doshes.” An English speaker can actually discern quite a lot of information from this sentence, despite not knowing three of its four distinct words. It’s clear that a gostak is a singular noun, and not a proper one like a name; that distims is a verb in present tense, an action the gostak is taking; and that what’s being distimmed is not one dosh but several of them. We can further infer that the gostak is something capable of distimming, and that doshes are things that can be distimmed. Muckenhoupt noted that this structural information is exactly what you need to operate language in an interactive fiction. You don’t have to understand what distimming actually does to realize a command like DISTIM DOSH should be linguistically valid, or to type it at a prompt to see what happens.

The Gostak

An Interofgan Halpock

Copyright 2001 by Carl Muckenhoupt

(For a jallon, louk JALLON.)

Release 2 / Serial number 020305 / Inform v6.21 Library 6/10Delcot

This is the delcot of tondam, where gitches frike and duscats glake. Across from a tophthed curple, a gomway deaves to kiloff and kirf, gombing a samilen to its hoff.Crenned in the loff lutt are five glauds.

>frike

You’re no gitch.>glake

What do you want to glake?>duscat

You reb no duscats here. (A delcot without duscats? Hmm.)>reb

Delcot

This is the delcot of tondam, where gitches frike and duscats glake. Across from a tophthed curple, a gomway deaves to kiloff and kirf, gombing a samilen to its hoff.Crenned in the loff lutt are five glauds.

>reb glauds

Which do you mean, the raskable glaud, the poltive glaud, the glaud-with-roggler, the glaud of jenth or the Cobbic glaud?

Each verb you read is a potential experiment. In the excerpt above, the player learns only gitches can frike, and that glakeing requires a subject. “You reb no duscats here” implies reb might mean to see or to look, and further experiments seem to confirm this. Slowly, a basic vocabulary begins to accumulate.

Knowing parser IF conventions offers more clues. The line in the opening header “For a jallon, louk JALLON” mirrors invitations in other games to type the capitalized word for some introductory text (“For help, type HELP”). Typing jallon indeed brings up instructions, but written entirely in Gostakese—which nevertheless provides many further useful examples:

This is a halpock. As in all halpocks, you doatch at it about what to do in a camling by louking murr English dedges, and the halpock louks back. Durly, you could rask a chuld (if you rebbed one) by louking:

>RASK THE CHULD

Rasked.You could then tunk the chuld, or pob it at a tendo, or whatever:

>DURCH CHULD

Nothing heamy results.>POB MY CHULD AT THE GHARMY TENDO

The tendo leils it.You can use multiple objects with some dapes[…]

Since Muckenhoupt’s language borrows its foundation verbs like to be from English, as well as most prepositions and nondescriptive adjectives, an English speaker gets a lot of useful information with each sentence to help them start guessing the meaning of various words. In this exchange, the player figures out a verb meaning “to exit or leave”:

A warb degombs the brangy.

>degomb warb

I only understood you as far as wanting to degomb.>degomb

But you aren’t in anything currently.

In traditional parser games, you might need to make a map as you play. In The Gostak, you need to build a dictionary. The game is difficult or impossible to play without copious notes on words and their possible usages, filled with guesses, partial information, and out-of-context phrases:

darf = n. ?

darftunder = n. not poltive [alive]. has three coyds [brimny, clarby, statched]. If you durch it, it will tund a darf.

dass = ?

deave = “be”/exist? room/location?

dedge = word?command?

degomb = v. exit

delcot = r. place?

disbosh = response

distim = v. Just says “Distimmed,” no apparent change to item. Gostaks do this. State change? Can only do to something poltive [animate]

distunk = v. ? You can do this

doatch at = v. talk?. doatch at someone about something

dobbly = a.

droke = n. Whatever it is, it can talk. drokage = conversation

durch = v. causes a shamtag to flome

durly = a. sad??

duscat = n. dangerous animal. it can glake.Structural patterns help infer verbs not explicitly seen. For instance, you might observe that tunk and distunk appear to be opposites. If you encounter an adjective lelloed that means “closed,” might you be able to dislello something to open it? As players continue immersing themselves in the game’s strange lingo, in short order they’ll find themselves more or less following sentences like “A raskable glaud is about as unheamy as a darf of jenth, but at least it can vorl the doshery from the gitches,” and taking actions that cause the state of this curious world to change in predictable ways.

Crenned in the loff lutt are five glauds.

>rask raskable glaud

Rasked.>milm

You are rasking:

a raskable glaud

your shamtag (which is lelloed)>reb

[…] Crenned in the loff lutt are four glauds.>pob raskable glaud

Pobbed.>reb

[…] Crenned in the loff lutt are five glauds.

The game is carefully designed to help you learn how to play it, despite its seemingly obtuse surface. Nearly every verb mentioned in text is implemented so you can try it yourself, something rarely true in typical IF. Each new message is a chance to learn more vocabulary, with failures often more instructive than successes. Muckenhoupt wanted a key mechanic to be “words as treasures … learning a new verb is the reward for solving a puzzle.” You might have previously figured out how to acquire a whomm darf, for instance, with no idea what the adjective whomm means (or the noun darf, but never mind). Attempting to tunk (examine) it results in:

Snave, very snave. There’s so much koldgeon in this darf, you can’t tunk it for more than a camling.

You might not know all these words, but you may have figured out that camling seems to mean “one move” or “a moment.” If something koldgeon can’t be tunked for more than a camling (looked at for more than a moment), does koldgeon mean bright? Sure enough, if you take your whomm darf into an area where previously you couldn’t reb (look), the room is now described in full and you’re able to start exploring it.

But the world behind the words stays surprisingly fuzzy. Certain concepts seem at first like they map easily to familiar IF analogues, but sometimes further play questions these assumptions. Take movement, for instance: you quickly learn you can pell at (go?) a lutt (direction?) to change your location, and there seem to be various kinds of lutts that come in pairs like loff/hoff and jirf/kirf, apparently analogous to concepts like north/south. pell at the loff lutt thus seems to mean something akin to go east (literally, “go at the east direction”). But is that translation right? The lutts at times seem to behave more like physical objects than abstract concepts. You can pob (drop) things into them, for instance. To solve one puzzle you’ll need to pob a glaud into a lutt to prevent something called a pilter from pelling at that lutt and escaping you. Is directional movement somehow constrained through fixed points in this world, like portals? Does pelling even signify motion at all? Muckenhoupt remained cagey when asked: “Some of the words simply don’t correspond to anything that actually exists,” he noted. One reviewer wrote:

You might decide that a particular noun means, say, “water,” and later decide that a certain adjective means “wet,” and then belatedly discovered that your water isn’t wet—because the game doesn’t agree that those words have the relation you’ve assigned.

The resulting world is one you can glimpse only dimly, with logics and consequences that seem by turns familiar and alien. “It’s a tribute to the thoroughness of the implementation,” the same reviewer continued, that the world of The Gostak nevertheless “begins to take on some personality; obstacles and helpers don’t just serve their functions, they also have connotations, associations—this one is faintly ludicrous, that one is vaguely chummy, another one is not very bright but trusting.”

Parser games already take some effort to play; The Gostak requires more than almost any other, and the barrier to entry, to some, can be deeply off-putting. Released as part of the parser community’s seventh annual Interactive Fiction Competition, it ranked twenty-first out of fifty-one entries, only barely in the top half. Most participants admitted they didn’t even try to play it: “This may be very clever,” went one typical truncated review, “but I simply didn’t have the patience to finish it.” The final rankings revealed an extraordinary spread of scores from judges, with roughly equal numbers giving the game low, medium, and high marks. As of 2021 its scores still had the highest standard deviation (the amount of variance in a set of values) of any game ever entered in IF Comp across a quarter century of events.

Some players questioned whether The Gostak should be considered interactive fiction at all: if you couldn’t even understand the story you were operating, could it really be said to be fiction? But others appreciated the game’s unique “dream language,” with one reviewer comparing it to the novel Finnegan’s Wake for the way “you don’t just mechanically decipher individual words but also feel your way to the meaning of things based on rhythms and memories and word associations. Every time I poked and pushed at the game, I could feel a robust and consistent world there.… It’s the one game [in this year’s competition] I dreamed about.”

Fostin of the Morleon

The fostin is far too dobbly for the morleon, but then, that’s why it’s a fostin. You can reb the morleon from here.You can reb here a reggler and a chalm.

>tunk chalm

There’s a musny on the chalm: “NO GASKING”.>save

Ok.>gask chalm

You gask it until it’s blide, but it disgasks […]

Today The Gostak can be even trickier to play, with fewer players well-versed in the parser conventions on which its foundations for understanding were built. But for those who love a challenge, it’s absolutely still worth trying. It creates a uniquely literary kind of exploration that could never translate to a visual genre, perfectly suited to its textual medium. Its world is as hard to imagine as it is to forget.

You can play The Gostak online, or follow Carl on Mastodon. This chapter is part of “Further Explorations,” which you can get exclusively as part of the Collector’s Edition of 50 Years of Text Games, still available for preorder for a limited time (but the remaining copies are going fast!).

Stay subscribed here on Substack for more peeks at bonus book content and original research over the next few months. In the meantime, my friend Christopher Allen (who has been around the text, roleplaying, and board game scenes for many a year) has a modest Kickstarter about to finish for a new card-based tabletop roleplaying game called “Tableau.” I’ll repeat my own pull quote from the project page here:

“Tableau is a versatile, flexible framework for collaborative storygames grounded deep in the fundamentals of story and character. Mix and match cards to shift what themes, rules, archetypes, and ideas are on the table, helping your group tell a compelling and satisfying story.”

I was even involved a little bit in some of the prototyping, testing, and writing for this game. If you’re into the idea of a modular tabletop storytelling game, it’s definitely worth a look!

Finally, the Spring Thing Festival of Interactive Fiction is happening now; it’s a great way to see what kind of text games people are making today. Check it out, and stay tuned for more IF history here soon!

Love this! In a way, every game tutorial does some of this work--introducing concepts that may be unfamiliar by weaving them into plain English (or whatever language you are speaking). Only here, it's the whole game!

Aaron, thank you for this review and analysis of Carl Muckenhoupt’s The Gostak, it was seminal at the time. The gostak gestims the doshes. Why is this IF important? Well, you have told many more new people. I’m glad.